For more than 150 years photography has been about capturing and presenting reality. Whether using silver halides or CCDs, a photograph is thought of as a snapshot of some part of the world at a particular time with a particular point of view. We say things like “let me show you what happened on our vacation” or “Camino Real de Tierra adentro” as if photographs are unchanging proof of what was and how we saw it.

As every photographer secretly knows, there was never any stopping the development of silver halides once they had been exposed. It just took so much longer once fixer had been applied so that the missive to “keep the photograph out of the sun” was enough to make billions of people think of a photograph as a static document.

Today’s technology has steadily made photographs subject to more and more change downstream of the original shutter click. Digital photographs change rapidly and without any control. Every transmission between devices has the possibility of changing a photograph as each new device may have a new format, a new limitation, or a new set of possibilities. Every time a photograph is shown it is likely to be with a new meaning within a new context.

It may simply be better to think of a digital photograph as a kind of visual hint of what we once might have seen. Uploaded photographs are positively ephemeral (or is that ethereal?).

|

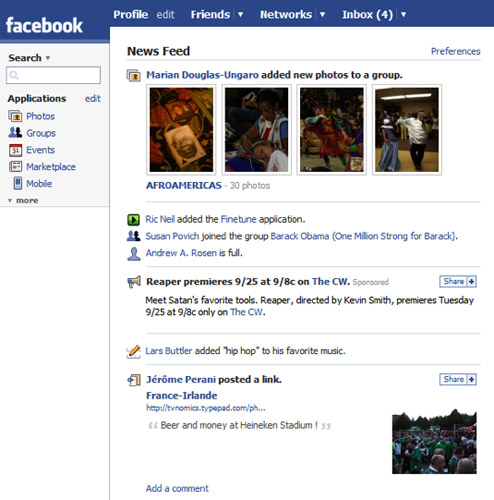

Take, for example, what happens if you use the Facebook online social network (www.facebook.com) to show others your photographs. According to press reports Facebook is growing at a phenomenal rate and is now delivering more than 10,000,000 photographs a day. Each photograph is reformatted and re-contextualized according to Facebook’s wishes without regard for what the photographer may have intended. The page with the photographs is created by software taking data and input from a large number of users who have no knowledge or intent with regards to the photographers. The software sizes, formats, colors, organizes, and orders photographs according to its own internal rules. Further, the system adds in metadata around the photograph which aids (or confuses!) the interpretation of the image. Similar things happen in all social online networks today.

So what does this mean to us as photographers?

Photographers must think of themselves as creators of visual imagery. Much like screenwriters, they are at the beginning of the process, but are rarely, if ever, involved at the end of the process where someone sees their work. This may be frustrating, but technology is steadily moving towards more disempowerment of content creators. Your frustrations are shared with writers, musicians, filmmakers, artists, and everyone else whose medium can be digitalized.

Photographers today may have some influence, but certainly not authority.

This is even more so given that photographs are now being used in so many unforeseen ways. Take, for example, the possibility of taking a photograph and turning it into an 3-dimensional avatar. Such technology is being worked on in several places and represents a very odd juxtaposition of reality and virtual reality. We take a photograph of a friend at a wedding taking place at a sacred ceremony. Later we upload it to the net and in return receive a extrapolated 3D model of our friend.

This new avatar is then animated to show emotions and doing activities in the virtual world which our friend may never have considered doing themselves. For example, you may have your friend/avatar interact with other avatars in ways wholly unacceptable in polite society. The original photographic memory from the wedding has no bearing whatsoever upon what its derivative is actually doing.

On the other hand photographs are far more widely distributed today than in the past. I regularly see hundreds of photographs from friends and colleagues today where in the past I might have seen one. Even widely published photographers such as our mentor, Pedro Meyer, are seeing their photographs distributed more widely and more rapidly than ever before. Facebook and its brethren have made photographic distribution nearly effortless.

Technology will continue to lower the barriers and costs associated with taking and distributing photographs. It won’t be long before we see cameras which never turn off, recording continuously for as long as the batteries last. Our job won’t really change, though, and we will continue to edit, contextualize, and frame our experiences using our skills as photographers.

For those of us interested in seeing photographs, does this mean that photographs no longer represent the original intent of the photographer? I would say that one should never believe in the veracity of any image (and any information displayed near an image) that you see. The need for having an informed critical point of view – on everything you see – has never been more important.

Peter Marx

pietro@evolutionary.com

September 2007

Los Angeles, California

**

Peter Marx is Adjunct Professor at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He is the former CTO of Vivendi-Universal Games and was the Vice President of Emerging Technologies for Universal Studios. |