"Questioning Perceptions"

***

|

Clouds © Pedro Meyer, 2004

|

|

We were about to land in Mexico City; I had my digital camera pointing out the window when over the loudspeakers a pre-recorded voice stated, “All electronic devices must now be turned off….” Which of course I thought did not actually include my camera. However, as the stewardess paced the corridor inspecting if all the passengers were following the orders just spoken from above, she let me know that they understood “all electronic devices” as including any digital cameras. By some misguided notion of bureaucratic expertise someone came to the conclusion that the pixels landing on a memory chip inside a camera could actually derail the communications gear on an airplane about to land. Well, they don’t. As soon as the stewardess walked past me to buckle herself down in her own seat, I took out my little Sony T1 digital camera to take some more aerial images, I knew there was no chance that my camera interfered with the communications of the plane, any more than the digital watch did, on the wrist of the passenger sitting next to me. We are constantly faced with issues of perception, or shall I say miss-perceptions in these tumultuous and complex times when so many fundamental notions of what we believe to be “true” are never really questioned and just taken as articles of faith. Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (planisferio 1) Oscar Guzmán © 2004 Deepak Chopra, in his audio book, New Physics of Healing, tells us about the Quantum mechanical body, in order to comprehend what it really is and how the latest advances in science determine a new way of perceiving even ourselves. He begins by exploring issues of perception and how these have determined and influenced how we treat nothing less than our own bodies. Upon facing for the first time the notions that Dr. Chopra explained in great detail, I was fascinated at the uncanny similarity to all the those concerns that photographers have been expressing with respect to digital photography and matters of representation. Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (planisferio 2) Oscar Guzmán © 2004 He explained how the mechanics of perception are frozen in an old worldview that should have gone away with Newtonian Physics. How does perception gets structured in our physiology? He asks. And goes on to explain how commitments are structured into our body mind by conditioned circumstances. Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (polar 1) Oscar Guzmán © 2004 In India for example, a baby elephant is tied with a flimsy rope to a green twig for a few weeks after it is born, but then when the animal grows up to become a full grown huge animal, if he were to be tied with an iron chain to a tree he could snap the iron chain with one movement or better yet even walk away with the entire tree. However, if the elephant is tied with a flimsy rope to a green twig it won’t be able to escape, it has made a commitment in his body mind that this is a prison and therefore will not escape as long as that flimsy rope is tied to his foot. At Harvard Medical School there was an experiment made some 20 years ago that ultimately led to a Nobel Prize in Physiology (1) . A group of kittens were brought up in an environment that had only horizontal stripes, and another group that only had vertical stripes. And when those kittens grew up to become “wise old cats”, as Deepak Chopra, amusingly called them, one group of cats could not see anything other than a horizontal world and the other group could not see anything else but a vertical world. They lost the sensory apparatus to see either horizontal or vertical stimuli. The visual sensors they had been brought up with now determined their world. Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (total 1) Oscar Guzmán © 2004 There are a great number of experiments with all of the data on the mechanics of perception now pointing to one crucial fact leading to the same conclusions; our sensory apparatus and our inter neuronal connections develop as result of our initial sensory experiences and how we are taught to interpret them, and subsequently we function with a nervous system that has only one reason for it’s existence, to reinforce what we were exposed to and was interpreted for us in the first place. There is a technical term for this used by psychologist, its “premature cognitive commitment”, we commit ourselves to a certain cognitive reality, a preconceived conceptual boundary, literally our nervous system serves to keep reinforcing the conceptual boundaries that we have structured in our own consciousness. The picture of the world turns out not to be the look of it at all, it’s just our way of looking at it, very literally, the shape, color or texture of things are the function of our receptors that have been programmed to be seen in a certain way. The eye cells of a bee, for instance, when it looks at a flower it doesn’t see the same colors that you and I see, because they do not have the receptor to see them. However, from a distance a bee can sense ultraviolet and thus the honey in a flower, yet it cannot see the flower at all. A bat would see such a flower as the echo of ultrasound, a snake would sense that flower as infrared radiation, a chameleon’s eyes balls would see on two different axis something that we can’t even remotely imagine. So then, what does the real world look like? Asks Deepak Chopra, What is the real texture of it? What is the real shape? And the answer he gives, is, there isn’t such as thing. There are only an infinite number of possibilities, all coexisting at the same time. Yet we freeze such fields of infinite possibilities into a certain perceptual reality, literally as a result of our cognition derived from our “premature cognitive commitments”. Sir John Carew Eccles (2), who also won the Nobel Prize amongst other things for elucidating the mechanics of perception stated: “ There are no colors in the real world, no smells, no textures, no sense, nothing of the sort, they are all structured in our awareness, they are all assembled in our awareness”. There is definitely a shift in the world of technology today, leading to the overthrow of a superstition that existed in science for a long time. That superstition is materialism. That the world out there is made out of objects that are separated from each other, and which can be separated from each other in space and time. Our entire system of logic is embedded in this system of materialism, which makes sensory perception the crucial test of reality.

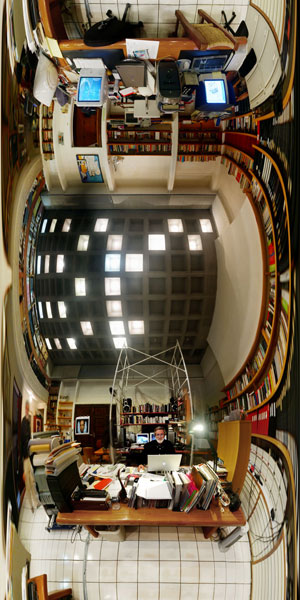

Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (vertical 1) Yet all our technology today is built on the Quantum mechanical perspective. Today anything that we do, such as using the telephone, or watching TV, or using a computer or traveling on a jet plane from here to there, or sending a missile into outer space, all of these are based, not on the idea of the atom as a solid entity but on the idea of the atom as a void of energy. So even though these transformations have taken place, the superstition still remains in place with respect to materialism. If this then is not really what this is in reality, then what is it? Everything that you really see is made out of atoms, these atoms are made out of particles, that are moving at lightening speed around huge empty spaces, and those particles themselves are not material objects but fluctuations of energy. If you could see the human body with the eyes of a physicist as it really is and not through the artifact of sensory perception, because that is what has been happening, we would come to the conclusion that we are into some major transformation in our perception of reality. Obviously the words spoken by Deepak Chopra struck a chord in me, with regard to photographic representations. More so then, when by one of those coincidences in life, I had the pleasant surprise of a visit to my studio of a friend who wanted me to meet someone who was doing some very interesting work that he felt I should see. Oscar Guzmán, who has been working over the past two decades in 3D environments, showed me his work, that unwittingly, connected me directly with the theme of multiple receptors commented upon by Dr. Chopra, only this time from the perspective of photography. Our potential to view the world in so many different ways became immediately apparent. The metaphor of the various forms of receptors by the bee, the bat, the snake and the chameleon, became all too eloquent. Oscar, pulled out his camera and took a portrait of me sitting at my desk in my studio, and then stitched those same images into so many different polar combinations, none of which in fact related to the optical representation that for centuries had been the sole method of photographic points of view. Thus giving visual forms to the words spoken by Deepak Chopra: “What is the real shape in the world? And the answer is, there isn’t such as thing. There are only an infinite number of possibilities, all coexisting at the same time.” I could perfectly well imagine myself traveling in that space made out of the void rather than atoms, that Dr. Chopra mentioned, as moving through those clouds as the plane was about to land, was a very magical representation of space and time, with that fluctuating energy all around me. Pedro

Meyer Please also read Oscar Guzman on “Visual Cartography” In the magazine section at ZoneZero. http://zonezero.com/magazine/articles/cartografia/cartography.html As always please joins us with your comments in our forums. Pedro Meyer at his desk in his studio (polar 2) Oscar Guzmán © 2004

|

|