It

was one of my first encounters with the new Argentine. I had just returned

to the country after seven years. Everything surprised me, spoke to me

of the nation's changes. At that time, Argentine did everything in her

power to prove she was no longer the one I had left, the one that had

killed so many. The new Argentine was the end result of those deaths:

that is why she did everything to avoid speaking of their lives.

It

was one of my first encounters with the new Argentine. I had just returned

to the country after seven years. Everything surprised me, spoke to me

of the nation's changes. At that time, Argentine did everything in her

power to prove she was no longer the one I had left, the one that had

killed so many. The new Argentine was the end result of those deaths:

that is why she did everything to avoid speaking of their lives.

However, that afternoon something of the new Argentine seemed to look at the old. That afternoon in the Colegio Nacional's auditorium, one or two hundred students, who seemed very young, asked us to tell them the story of those whose history seemed so far away to them.

It was 1984. Not much time had passed, but for these young Argentines, those young Argentines were, at the most, the details of a myth. A myth does not generally specify details. It does not display them. It does not need them. Neither did this one. The myth of those years was made up of general statements: angels or devils in undefined circumstances, collective figures without a personal story. That aftenoon in the auditorium, these students did not quite believe that those students had been so similar to them, that it was just by chance that we lived in times when decisions were more wrenching, when the human will seemed capable of moving certain mountains.

That afternoon hardly lasted. It was followed by long silences, and it took us twelve years to return to the school. It was not by chance.

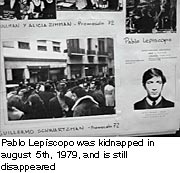

Generally

during those years, our dead companions were left without their own story.

We remembered them, primarily, in some marches against their murderers

and on the anniversaries of their kidnappings, when, their faces were

in the newspapers. It was as if what was left of them was mainly their

deaths.There is a poem by Louis Aragon about the dead of the French Resistance:

Generally

during those years, our dead companions were left without their own story.

We remembered them, primarily, in some marches against their murderers

and on the anniversaries of their kidnappings, when, their faces were

in the newspapers. It was as if what was left of them was mainly their

deaths.There is a poem by Louis Aragon about the dead of the French Resistance:

"Now you are no more/ than an inscription in our squares./ Now the memory

of your loves/is becoming blurred./Now you only are/because you died."

This meant something: it was very hard to discuss those politics. It was very hard to speak from the sacredness of democracy about a time when democracy was, at most, an instrumental value. And to avoid speaking of them as subjects who had made a political choice, it was better to turn them into victims, into the objects of other people's decisions –some bad men who had gone to get them in their homes because bad men are like that and do such things.

Through

the bad men's action our companions became disappeared, and in our stories

without history we made them disappear a second time; we took their lives

from them. We spoke of how they were the objects of kidnapping, torture,

and murder, and we barely spoke of how they were when they were subjects,

when they chose to live destinies that included the danger of death because

they felt they had to do so. Those versions of history were, among other

things, a way to disappear the disappeared

yet again.

Through

the bad men's action our companions became disappeared, and in our stories

without history we made them disappear a second time; we took their lives

from them. We spoke of how they were the objects of kidnapping, torture,

and murder, and we barely spoke of how they were when they were subjects,

when they chose to live destinies that included the danger of death because

they felt they had to do so. Those versions of history were, among other

things, a way to disappear the disappeared

yet again.

It may have taken us a while, but in the end we realized that all of us disappeared with that second disappearance. Our stories were lost with theirs, which no one told. The first disappearance, the cruelest one, was inevitable.

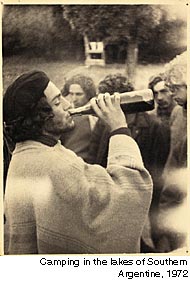

The second was not. We needed to reconstruct their stories. We had to tell the stories and tell ourselves that all of them were people more than they were victims, and that, long before and more positively than their deaths, all of them had lives.

Just recently, we have now been able to remember again. In a variety of spaces and sectors, individually and in groups, in the most diverse ways, we are putting together a story.

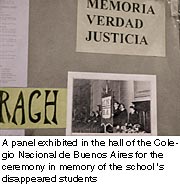

In late 1996, at the Colegio Nacional, we held an exhibit in memory of

those students, a ceremony, more or less pertinent words, hugs, and memories.

That night, in halls that were no longer so big, Marcelo Brodsky's pictures

were, perhaps, the clearest link, the most visible one.

Photography plays a privileged role in this effort. Photography is not

supposed to tell; it shows. If a picture says we exist we must exist.

Photography plays a privileged role in this effort. Photography is not

supposed to tell; it shows. If a picture says we exist we must exist.

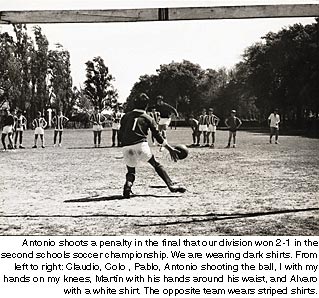

Photography journeys through history, against time. Photography is an always vain attempt to stop time, to formulate errors in its flow. In each picture, what is no more and will never be again is presented as though it still were, with the lasting bloom of flowers on wallpaper. We are seized, momentarily, by the puzzlement of facing the lost, by the emotion of this encounter. Sadness comes later.

Photography is always cruel. It sets the clarity of its impotence before

us.Thing which is even more true in this case. Telling history, telling

ourselves our stories, does not mean reviving those days.

These faces that Brodsky reproduces,confronted with today's faces or with their absences do not speak only of the passage of time in each one of them. The time that passed there is not just individual, it is an era.

Fortunately, that impotence is relative. Telling, showing that era does not mean reviving it, but I suppose we must recover it in order to live this one.

Today is another epoch, so different and so similar. I would like to think that this era is made, among other things, of this confrontation, of the way in which those faces, what Argentine was back then and what Argentine is now, confront one another and speak, and sometimes even, almost without noticing it, come to some agreement.