|

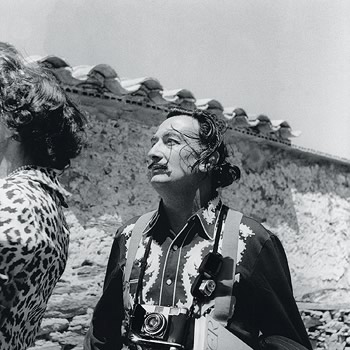

SUITE PORTLLIGAT: PHOTODOCUMENTS

In the same way that automatic writing enabled unforeseen poetic associations to be revealed, so photography provided a way for the Surrealists to fix the unconscious of the gaze. Dalí was attracted very early on by the transformative capacity of the camera, and essays like ‘Photography, Pure Creation of the Mind’ (L’amic de les arts, 1927) bear witness to this fascination. During the thirties, pictorical interventions on different photos and various collages help us comprehend the powerful influence of the photographic vision on the Dalinian oeuvre as a while. On the other hand the mythomaniacal character and calculated eccentricity of the man favored the persistent hovering around of different photographers, among whom we might single out, for their magnificent portraits, Man Ray, Brassaï, Cecil Beaton and Philippe Halsman. The photo album found in the Portlligat house after his death contains a total of 8,000 images, which serve to demonstrate the attention given to a vernacular and prosaic use of photography; in short, as the art historian Estrella de Dedo has pointed out, “for the documentation of obscure quotidianity as another manifestation of the Surrealist sensibility.” 1 The Centro de Estudios Dalinianos has taken great pains to catalog and study this material, which the Fundación Gala-Dalí plans to present in various instalments. In fact a photographic exhibition in the Casino Menestral Figuerenc a while back, based on the Melitón Pascua collection, displayed a number of prints of the unmistakeable rugged landscape of Cabo de Creus, in some cases with lines executed in ink, as if these were sketches of the series of rocky phantasmagorias. While the authorship of these lines is beyond doubt, we may ask ourselves who held the camera, however. Members of the artist’s inner circle such as Melitón himself, or Pitu Sala, the Cadaqués fisherman-philosopher cited in the prose of Josep Pla, dispel any doubt. Also famous for having checkmated Duchamp several times, Pitu even claims to have witnessed a number of shooting sessions. The photos, they explain, were usually taken with a Kodak Retina II-C during walks along the coast “while the Divine One delivered a monolog on the cosmic equilibrium of Easter eggs or on the non-Euclidian movements of the cavalry in the Battle of Tetuán.” Another set of photos, found among the probable belongings of Gala in the Púbol residence, turns out to be thematically more mixed, but it enables us to make out many of the artist’s obsessions – objets-trouvés, visual paradoxes, soft watches, scatological situations – as well as details of the avant-la-lettre Vinçon-style designer furniture that would delight Javier Mercadal or Oscar Busquets today. These essentially private documents, though not devoid of a particular oneiric quality, are pure, direct photos lacking in artificiality. Proceeding from a mechanical and objective neutrality, the camera is recreated in a hyperreal recording of the object, which was thus able to emit its symbolic density. “The Retina’s Schneider-Kreuznach lens guaranteed the necessary paranoia-critical definition,” 2 concludes Dr. William Jeffet, chief conservationist of the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, who has become the foremost authority on the matter.

1. Dedo, Estrella de: L’amour fou et l’amour sage: documentos fotográficos del Surrealismo, CCCB, Barcelona, 1997. 2. Jeffet, William: The Legacy of the Lentils in Dalí, S.D.M., St. Petersburg, Florida.

|