If photography is the art

of fixing a shadow, glass is the medium that transfers shadows onto

film. For Joel-Peter Witkin, whose elaborate tableaux reverberate

with the extreme conditions of life and death, glass holds powerful

associations. "Oldenberg," says Witkin, "once described

glass as 'lightning trapped in sand.' " A day before the New

York opening of Witkin's retrospective exhibition at the Guggenheim

Museum, he spoke with Michael Sand about photography, morality,

and human remains.

GLASS

My father had four brothers, all

glaziers, and he would include me in their work. The first job we

had was to take two-by-fours and break industrial glass, which he

would replace. So my job was to break the glass. Of course, we had

no goggles, no safety precautions. In the first two or three hours

or so, I got a splinter in my eye. And he took it out. His hands were

huge. He rolled my eyelash up with a wooden match--his hands smelled

of putty, cigars, and dirt--and he took the splinter out. The splinter

was in the white of my eye, and I was going crazy. Still, this was

closest communication I had with my father, except when he would come

over to the house and talk to my mother. They'd talk about money and

things like that, because he had to pay alimony. He would visit later

on, too, and show strange photographs.

He took me aside and showed me some clips from Life

magazine or Look magazine, the Daily Mirror, or the News (he wasn't

a New York Times reader). I was about five, and I knew when he was

showing me these photographs that he was telling me he couldn't do

this, but maybe there was a chance that part of him could, somehow,

through me. Without saying it, I looked at him, and I knew, and he

knew, that I could try.

I think that what makes a photograph so powerful is

the fact that, as opposed to other forms, like video or motion pictures,

it is about stillness. I think the reason a person becomes a photographer

is because they want to take it all and compress it into one particular

stillness. When you really want to say something to someone, you grab

them, you hold them, you embrace them. That's what happens in this

still form.

GLASS MAN

We're born naked. We actually

should live naked--not literally, but in terms of honesty and openness.

I've seen hundreds of people on the slab, and occasionally I see a

beautiful woman, who is still beautiful--and it's very, very shocking.

It has an impact, because you're seeing human remains, a human life,

or the evidence of it.

I stayed in Mexico City for four extra days when I

was making Glass Man, because I wasn't getting the bodies I wanted.

When bodies are brought in from the street, there's sometimes a doubt

as to how the person died. Street people may be found days later,

which makes it hard to determine the cause.

Drivers from the morgue make runs every day in white

trucks to pick up the dead. When found, the bodies are just thrown

on the gurneys, face-down. Their noses get broken. The trucks are

loaded with maybe six people, and they just lie on top of each other,

somewhat bloated. They're all stretched out. Their identities are

taken, their clothes are taken away, and records are kept.

When I stayed those extra days in Mexico, I knew something

was going to happen. I got a call. Four men were picked up, the last

run, on the last day before I was going to leave. I went down to the

hospital with my interpreter and went in to shoot. One guy had been

run over by a car, not in good shape. The other guy was an old man,

no good. One man had been stabbed to death. None of these guys had

his nose broken, because they took the trouble not to do that, for

me. The other guy, he was a real punk, nothing good visually.

For some people, the evidence of their spirit is either

there or not there in death. Nonetheless, when I saw this last guy,

I said, "I want him." This was just about Christmas-time,

so the Mexicans were outside celebrating, getting ready to take their

vacations.

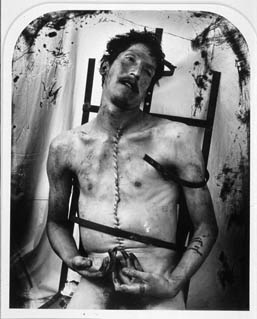

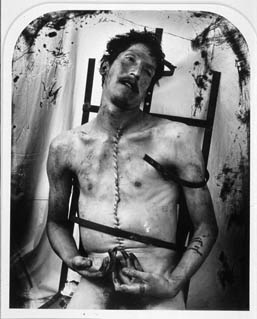

I'm in this room with a dead guy. I'm propping him

up, and I put a fish in his hand as a kind of prop, and I'm checking

the lighting. Then I get that straight, and I take a few photographs,

just as a kind of a record. Then I make arrangements to have the guy

autopsied. And as soon as he's being autopsied, he starts changing!

He's on the table, and he's changing. I turn to my Mexican translator,

who is a very, very bright man, and we have seen the same thing. He

says, "He's being judged. This guy is being judged right now."

Suddenly, he's not a punk any more. He's gone through this kind of

transfiguration on the table, on the autopsy table. I say to the technician,

"Don't wash him down. I want all the blood from the suturing."

Usually, they open up the skull and remove the brain. Sometimes they

put the brain back. Other times they put a piece of towel or paper

in there, or perhaps the Daily News--to maintain the form of the flesh.

In this case they put the brain back . When they were carrying the

brain, I said, "Look at this brain--it may have contained thoughts

of evil, but however he was judged, he is now a different presence!"

When I got him back, and I put him in this room, I

got him on this chair, and I photographed him sitting down. Then I

spent an hour and a half with him, and after that, he looked like

a Saint Sebastian. He looked like a person who had grace. His fingers,

I swear to God, had grown 50 percent. They were elegant. They were

the longest fingers on a man I've ever seen. It was as if they were

reaching for eternity.

MORALITY AND MORTALITY

I think most people aren't aware

that mortality has to do with life and death. Of course, not all of

it is about mortal toil. But it's about what happens in life. The

mortuary, not coincidentally, is the place for the mortal remains.

Every moment is a moral decision. I believe there's

a moral codex in each of our hearts, and it's a question of us finding

our destinies and the purpose of that destiny. This life is a testing

ground. It should be a sublime testing ground.

Seamus Heaney, who just won the Nobel Prize for Literature,

said that "The end of art is peace." It's a wonderful statement.

The reason we go to museums and the reason we look at beautiful things

is that there's not much out there that's beautiful any more. I think

of museums as new kinds of religious centers, as spiritual centers

of the secular life.

There's this great story I know about a wanderer somewhere

in a desert. He's walking along, and he hears the smashing of steel

and rocks in the distance. He goes out there to where the sound is,

and two men are crushing stones in the heat. He approaches one, who

seems very, very angry, and he's cursing. The wanderer goes up to

him and says, "What are you doing?" The man says, "I'm

breaking the stones." The wanderer approaches the other man.

This one is also smashing rocks, but he's not angry. The wanderer

says, "What are you doing?" The man responds, "I'm

building a cathedral."

Michael Sand

_______________

Originally pubished in World Art 1/96, and posted here by permission.

Michael Sand is a free lance editor working and living in New York

and can be reached at sandline@aol.com

Related Links

|