|

|

II Eventually, the Bush administration contributed to the re-politicization of art. Why? All the values and principles they chose to target were at the core of art practice including, freedom of speech, civil liberties, cultural diversity and tolerance, the right to dissent and criticize power. Since most institutional spaces were closed to critical art, virtual space became the de facto territory of contestation. A new anonymous political arts movement began to emerge as unsigned posters, hilarious political cartoons and outrageous PhotoShop images and QuickTime movies critical of Bush and his few international collaborators circulated in virtual space. After a group of poets rejected a Faustian invitation by the First Lady to read their poetry in the White House, a huge anti-war poetry website came into fruition. For a while, it was the most visited literary website ever. By early 2003, as we approached the irrational invasion of Iraq, sectors in the intellectual community and even the pop music and the Hollywood establishment began to finally break the silence. It warmed our hearts to hear celebrities like Susan Sarandon, Harry Belafonte, Martin Sheen, Danny Glover, and even the Dixie Chicks speak their minds. In mid February over 20 million people across the globe, demonstrated energetically against the war. Many artists, students and intellectuals who normally don't walk the political streets were there, along with myriad unlikely colleagues including housewives, senior citizens, war veterans and even apolitical citizens who had recently lost their jobs due to Bush's narrow-minded politics. Most demonstrations were peaceful and quite imaginative, in terms of their performance strategies, visual languages and poetic slogans. A window of hope seemed to temporarily open up in the smoky horizon. III Artists, arts administrators, curators, and producers are now facing many predicaments. Due to the drastic funding cuts, cultural institutions have had to trim down considerably their programs and staff, and most grassroots institutions and alternative art spaces face probable extinction within the next two years. Every week, we hear of yet another arts organization, museum department or community center that just lost its funding; of yet another arts administrator, or artist colleague who was just fired. Commissions and tours are being cancelled left and right. Our organization, La Pocha Nostra, alone has lost 10 large commissions since 9/11 and as of November of 2003, 70% of our budget is coming from our International touring. The toll that the Bush era is taking on people's mental and physical health is immense. Understandably, everyone is exhausted, poor, overworked and scared shitless of the immediate future; our communities are all in disarray and we don't even have a political project at hand to envision an alternative. It is no coincidence that in the last two years personal illness, divorce, and suicide against a backdrop of social, racial and military violence have all increased exponentially. Understandably, our bodies and psyches are internalizing the pain of the larger socio-political body and the confusion of the collective psyche. These dramatic conditions are forcing our frail arts communities to engage in serious soul searching and tough questioning: All across the US, in every art space, gallery, theater; bohemian café, recording and rehearsal studio, we are all expressing our perplexity and asking similar questions: What are our new roles as artists and intellectuals in this cartography of terror? How do we restore the mirror of critical culture for society to see, once again, its own ethical reflection? Are critical artists an endangered species in the US? Do we wish to live in a country without museums, galleries, theaters, cultural centers, literary journals, film festivals and an alternative press? If America continues to follow this path and chooses to become a closed society and a cultural wasteland, will we be able to tolerate living here as complete outcasts or will we be forced to become expatriates in Europe, Canada or Mexico? What concrete actions can we realistically undertake as a sector (and not as disenfranchised individuals), to reclaim our stolen civic self and our legitimate right to create, and articulate our artistic visions? How to keep these questions alive, discuss survival strategies with our local and national communities and present our case empathetically to the press and to sympathetic members of the political class? IV Since 9/11, I have had this reoccurring dream. I dream of a faraway country in which artists are respected in the same way pop celebrities, military men and sportsmen are respected in our country. Artists perceive a decent salary, own their homes and cars, enjoy vacations, and have medical insurance. The media and the political class value their opinions. They perform multiple social roles as social critics and chroniclers, advisers, intercultural diplomats, community brokers, and spiritual leaders. In this sui generis society, we can actually purchase poetry books and art magazines in convenience stores. Writers, philosophers, and performance artists appear daily on national television and radio. Museums are free and every neighborhood has a cultural center. In this most unusual society, even corporations, city councils, school districts and hospitals hire artists as advisers, and animators. In this imaginary society, artists don't have to write texts like this one.

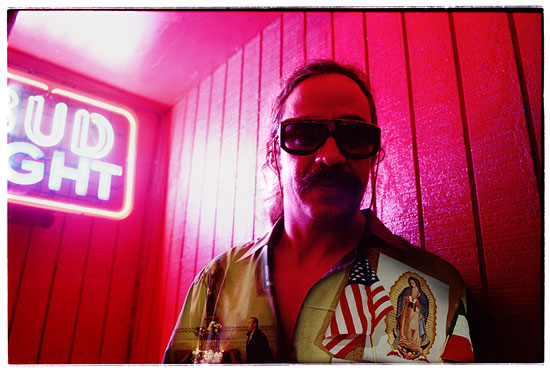

Guillermo Gómez-Peña.

|