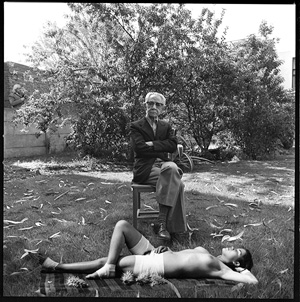

The most renowned photographer in the history of Latin America, Manuel Alvarez Bravo is the cornerstone of this art in Mexico. When he began photographing in the 1920s and 1930s, artists who constitute a veritable “who’s who” of the lens immediately acknowledged his innate capacity: Edward Weston, Tina Modotti, Paul Strand, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. The respect that he engendered was encapsulated in Cartier-Bresson’s response when someone likened Alvarez Bravo’s imagery to Weston’s: “Don’t compare them, Manuel is the real artist.” Alvarez Bravo’s unique eye was such that the founder of surrealism, André Breton, sought him out in 1938 to commission an image for the cover of a surrealist exhibition catalogue (he complied with the famous La buena fama durmiendo [The Good Reputation Sleeping], but it could not appear on the cover because of the full-frontal nudity). His recognition by such luminaries notwithstanding, Alvarez Bravo had little visibility within the U.S. prior to the modest 1971 exhibit at the Pasadena Art Museum in California, which later passed through New York’s Museum of Modern Art without causing much of a stir. Subsequent exhibitions at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. (1978) and San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Arts (1990) made Alvarez Bravo a much more familiar figure, and his consecration was assured when he returned to the MOMA in 1997 for the definitive exhibit of 175 photographs.

When Alvarez Bravo began photographing in the 1920s, the cultural effervescence that followed the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) had unleashed a national search for identity, and the question of what to do with Mexico’s inherent exoticism was the burning issue for photographers. Perhaps influenced by his relationship with Weston and Modotti, Alvarez Bravo was the first Mexican photographer to take a militantly anti-picturesque stance, and he achieved international recognition for work which reached creative heights from the late 1920s through the mid-1950s, a period during which he perfected a sophisticated approach to representing his culture. Conscious both of Mexico’s otherness and the way in which that has led almost naturally to stereotypical imagery, Alvarez Bravo has always swum counter to the stream of established clichés, using visual irony to contradict what he initially appears to saying, hence inviting the viewer to engage in the task of interpretation.

Consider Sed pública (Public Thirst), the 1934 photo of a boy drinking water from a village well. This image contains all the elements necessary to make it picturesque: a young peasant, dressed in the white clothing typical of his culture, perches on a battered village well to drink the water which flows from it; an adobe wall behind provides texture. But, the light in the image seems to concentrate itself on the foot that juts forward into the frame, a foot that is too particular, too individual to be able to “stand for” the Mexican peasantry, and thus represent their other-worldliness. It is this boy’s foot, not a typical peasant’s foot, and it goes against the expectations of picturesqueness raised by the other elements, “saving” the image through its very particularity.

A similar tactic can be observed in Señor de Papantla (Man from Papantla, 1934), where an Indian stands with his back to the wall, facing the camera. Here, as with the image of the boy, the objective elements in the photo would seem to make it picturesque: white peasant clothing, bare feet, and adobe walls, as well as a sombrero and bag woven of reeds. But, having awakened our anticipation of the exotic, Alvarez Bravo cuts back against it with an artistry that rejects the facile. The man refuses to dignify the camera by returning its look. It is often felt that the esthetic strategy in which the subject “retorts” the camera’s gaze is that which most effectively represents people at their most active, because it negates somewhat the camera’s tendency to reduce them to objects. But here, Alvarez Bravo gives us another turn of the screw by presenting us with an Indian who, in looking away, seems to say disparagingly: “Take all the pictures you want, outsider. Who cares what you do?”

Sed pública. Manuel Alvarez Bravo 1933 |

Señor de Papantla. Manuel Alvarez Bravo 1934 |

Alvarez Bravo’s search for mexicanidad (Mexicanness) led him to reconfigure national symbols. For example, Arena y pinitos (Sand and Pines) is an early image from the 1920s that demonstrates that a young Alvarez Bravo was much influenced not only by pictorialism, but also by the then pervasive interest in Japanese art. Infusing international art forms with Mexican meaning, Alvarez Bravo creates the background to his “bonsai” with what is in essence a mini-Popocatepetl, one of the volcanoes that dominate the Valley of Mexico. Another example is the 1927 photo of a rolled-up mattress, Colchón (Mattress). Here, he chose not to use the beautifully textured, folkloric petate which, woven of wide reeds, provided depth to the still lives created by Modotti and Weston. Instead, Alvarez Bravo photographed a modern mattress, but with the twist that its bands of shading make it look like the well-known Saltillo sarapes. In his recurrent imagery of the maguey cactus we can see his interest in playing with a ubiquitous symbol of Mexican culture; in one photo he “modernizes” the maguey by making it appear as if the central flower stem that sprouts from these plants has been converted into a television antenna.

Maguey

y pared dentada. Manuel Alvarez Bravo 1976

|

Obrero en huelga, asesinado. Manuel Alvarez Bravo 1934 |

The politics of Alvarez Bravo are always talked about in relation to his most famous photograph, Obrero en huelga, asesinado (Striking Worker, Assassinated, 1934). Nonetheless, while it is certainly true that he rejects officialist nationalism as completely as he does the picturesque, this image is problematic: its meaning is determined by the title ascribed to it, which may have been influenced by Alvarez Bravo’s involvement in LEAR (League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists) during the 1930s. I would argue instead that the politics of Alvarez Bravo -- and his search for Mexico’s essence --could better be found in the ways he represents the daily life activities of humble people, rather than in overt social commentary. His imagery is a modest, almost transparent portrayal of individuals who he seems to have “found” within their natural habitats rather than to have “created” through conspicuous visual rhetoric. A very understated esthetic that avoids overt expressivity, Alvarez Bravo’s is an all but invisible technique designed to capture anonymous people in ordinary activities, where they are neither romanticized nor sentimentalized. A perfect instance is La mamá del bolero y el bolero (The Mother of the Shoeshine Boy and the Shoeshine Boy), an exquisite image from the 1950s in which a mother visits her son to bring him lunch, and eats with him while he rests from his tasks of shining shoes.

Manuel Alvarez Bravo has been a definitive influence on Mexican and Latin American photography. His rejection of facile picturesqueness, his insistently ambiguous irony, and his redemption of common folk and their daily subsistence have marked out a path of high standards for photographers from his area.

Capsule Biography

Born in Mexico City, 4 February 1902. Attended Catholic school from 1908 to 1914, but left in 1915 to work. Begins to educate self in photography, asking advice from photography suppliers, and learning English by reading the labels on developer bottles. The 1923 arrival of Edward Weston and Tina Modotti are crucial to Alvarez Bravo’s development, and he buys his first camera in 1924. Wins first major award in 1931, and decides to pursue photography as full-time career, in part as a still photographer in cinema productions. Meets André Breton in 1939, and his work is included in a Paris Surrealist exhibit. In 1942, the Museum of Modern Art (New York) acquired their first works by Alvarez Bravo and, in 1955, his photographs were included in Edward Steichen’s Family of Man. During 1959, Alvarez Bravo stopped working in the film industry, and became the photographer of important art books for the Fondo Editorial de la Plástica Mexicana, of which he was a founder. Alvarez Bravo left the Fondo in 1980 to work with the Mexican-based media empire, Televisa, where his collection of photography was exhibited and published in a three-volume set. In 1996, Alvarez Bravo’s collection moved to the newly created Centro Fotográfico Alvarez Bravo in Oaxaca City, Mexico.

John Mraz

Go to: Happy 100th Birthday Manuel Alvarez Bravo!!

Send your comments on this review to: mraz.john@gmail.com