|

Murals are the art form that reflect most clearly any changes in the

sociopolitical environment. From the time of the Renaissance, murals

have laid out in visual form the ideology of their sponsors, be it the

Church, the government, a powerful opposition, or simply private patrons.

After the Mexican Revolution of 1917, when the new government desired

to promulgate its revised version of Mexican history, muralism was revived

as a means of visually representing the point of view of "the revolution."

Artists were commissioned to adorn public buildings with heroic images

of the newly victorious underclass and its cultural history, pre-conquest

civilization. In its new role as a tool of historical revisionism and

cultural reclamation, murals have accompanied 20th-century anti-colonialist

and anti-bourgeois revolutionary movements around the world, though

never again with the kind of massive government support that existed

in Mexico in the 1920s.

Muralism was revived in the United States by the example of three great

Mexican muralists: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David

Alfaro Siqueiros.1 These three renowned artists came to the United States

in the early 1930s when a more conservative government took power in

Mexico and reduced its government patronage. During the Depression years,

United States artists inspired by the Mexicans persuaded Franklin Delano

Roosevelt to begin a mural program as part of the New Deal, but with

a few exceptions, the works were unprovocative and unremarkable. Nevertheless,

their presence in post offices and public buildings, as well as the

Mexican precedent, helped provide the impetus for the community mural

movement of the 1960s, which accompanied the strikes, marches, and demonstrations

of the Civil Rights and anti-war movements.

Unlike all previous mural movements, which were government sponsored,

the community murals of the late 1960s began as an arm of struggle--unfunded

and unofficial--a way of claiming urban space for a particular group

or point of view. From the beginning, a large proportion of the artists

were professionals, often young art school graduates from African American

and Mexican American backgrounds, or European American New Left activists,

using their skills to aid political movements. These trained artists

worked with neighborhood residents and youth to create murals and to

stimulate self-taught artists to join the mural movement.

In the case of Chicano murals, the catalyzing event was the United

Farm Workers (UFW) union organizing drive and a corresponding cultural

movement toward a politically defined identity. While posters and banners

were important elements of new militant art, the use of the mural form

was encouraged by the existence of a strong Mexican mural tradition.2

In the same way that the Chicano movement itself developed in two overlapping

directions, one emphasizing cultural identity and the other political

action, the imagery of early murals was drawn from both of these sources.

Imagery in cultural murals included copies of Mayan murals, pyramids,

Olmec sculptures, Indians (historical, mythical, and Hollywood), the

tripartite head (Indian, Spanish, and Mestizo), and religious motifs,

particularly the Virgin of Guadalupe. Political murals tended to emphasize

Mexican history, oppressed workers, portraits of political leaders like

Cesar Chavez and Reies Lopez Tijerina, as well as Emiliano Zapata and

"Pancho" Villa--heroes of the Mexican revolution. Solidarity figures

from other revolutions, like Ché Guevara and Martin Luther King,

Jr., were also frequently depicted. At Chicano demonstrations, the UFW

flag and the Virgin of Guadalupe were omnipresent as identifying icons.

These early murals, filled with political and cultural imagery, were

similar in origin and themes to the republican murals of the north of

Ireland. Chicano mural painters, however, even from the beginning, placed

much more emphasis on artistic quality and complex painting. This was

due to the large proportion of professionally trained artists involved

in mural making, the importance and popularity of the Mexican mural

tradition, and its wide dissemination to those with less skill. For

example, the film Walls of Fire, about the murals of Siqueiros, was

widely shown during this period, and many murals borrowed heavily from

this source. Also, from the early 1970s, some monies were available

to pay muralists (or at least buy supplies) through grass-roots fundraising,

small grants, and creative use of anti-poverty and social service funds.

Another difference between the Irish republican murals and the Chicano

walls, even in this early period, was the need of the Chicano movement

to address internal problems like gang violence, drugs and other self-destructive

behavior attributed to racism and poverty, while at the same time continuing

the struggle against external oppressive forces. Muralists approached

this issue in several ways. There were impassioned pleas against the

constant killings, like "To ace out a home boy from another barrio is

to kill La Raza," as well as murals painted by youth gangs to honor

the dead and mark a truce. At the same time, there were works glorifying

street culture: pachuco and pachuca style, low rider cars, graffiti,

Spanglish, and "bad taste," like the use of garish color combinations.3

These works were aimed at raising self-esteem and combating racist stereotypes

by glorifying precisely what was condemned by mainstream America.

During this early, nationalist period, 1970&endash;75, monocultural

groups predominated. Although Chicano muralists from one city would

often help out others in big projects, there was little racial mixing

during this period. At Chicano Park in San Diego, for example, land

underneath the Coronado Bay Bridge was taken by militants for a people's

park in 1970. Part of the plan was to muralize the freeway pillars.

During the first few years, several freeway offramps, walls, and pillars

were painted by local artists and residents and later by artists from

Sacramento. But until 1977, all the artists involved in the San Diego

project were Latino.4 In Los Angeles, mural projects were organized

in two housing projects, Ramona Gardens and Estrada Courts. All of these

projects were locally controlled and funded during this period with

the assistance of the community arts centers (like Centro Cultural de

la Raza in San Diego, or the Mechicano Art Center and Goez Gallery in

Los Angeles), which organized these activities.

Some of the self-taught artists found the mural medium compatible with

their abilities, and felt that their work was of immense value to the

local community, which led to their identification as muralists. In

1976, the first national meeting of these self-identified muralists

took place in New York City. This sense of identity, of belonging to

a larger group, was reinforced by the publication of a newsletter and

two books from inside the movement.5 There are some indications that

such an incipient identification of wall painters as muralists may also

be occurring in Northern Ireland. In his book Drawing Support: Murals

in the North of Ireland, Bill Rolston describes the work of one such

artist, Gerard Kelly. While spending time in prison as a POW, Kelly

studied art and began to paint murals on his release --he is now responsible

for a considerable number of outstanding murals in his neighborhood.

As Kelly says, ". . . most people like art . . . people would stand

and look at a mural before they would read a paper. Also, it gives the

people of the immediate area a sense of pride."6 Such artists tend to

continue to paint murals beyond the struggle period and transform a

momentary explosion into a continuing people's art movement. When the

heat of the Chicano movement (and the New Left opposition in general)

began to cool in the mid-1970s, many of the artists who had been involved

in militant work began to move towards more personal expressions and

reintegrate into the gallery system. Others who had identified as muralists

felt the power of their work in the community in terms not only as a

call to struggle, but also as fulfilling a need for relevant art in

ordinary people's lives that spoke to their pride and their neighborhood.

If Irish muralists continue to create community art beyond the peace,

perhaps this pattern will be duplicated in Ireland.

As muralists moved away from militant imagery (following the general

mood of a post-Vietnam society) toward portrayals of self-pride and

unity, the nationalist phase of the mural movement ended and the institutional

phase began. Murals had become respectable. They were funded by grants

from the new National Endowment for the Arts, which had a special program

to encourage community arts organizations, city funds, and, briefly

but massively, from CETA (Comprehensive Employment Training Act). These

latter funds were abruptly terminated with the election of Ronald Reagan

in 1980. CETA hired unemployed artists to set up public-service-oriented

arts service organizations in cities throughout the country. This general

employment program was responsible for a great influx of new artists

to the field of community murals. The new mural organizations were multiethnic,

and because city funds were often involved, mural content was controlled.

More often than not, this was through self-censorship and community

requests for noncontroversial subject matter rather than government

interference. Positive images of unity, ethnic pride, and history were

the most common themes, although whales and other environmental issues

formed an important subgroup.

Typical of these new organizations was SPARC (Social and Public Art

Resource Center), headed by Chicana muralist Judy Baca, which used public

funds along with private grants to finance murals by artists from various

ethnic and racial backgrounds. In 1976, Baca and SPARC began a massive

project that reflected the new multicultural emphasis. The Great Wall

of Los Angeles is devoted to the experience of different ethnic groups

in the history of California. It covers more than a half mile of the

wall along a concrete flood control channel and, under the supervision

of Baca, was painted over five summers by large crews of ethnically

and culturally diverse artists and teenagers. Since 1989, SPARC has

managed a city-funded mural program, Neighborhood Pride, which has produced

six to ten new murals each year in different ethnic communities of Los

Angeles.

Although community murals had become an accepted art form by the mid-1970s,

there was still a significant split between minority, mainly Chicano

and black artists, and a more art world-oriented group of "public artists"

who were working in abstract and photorealist styles that were being

incorporated into "urban renewal" and downtown revitalization projects.

By the mid-1980s, with the decline of an activist political base and

the introduction of significant funds to public art (as more and more

cities passed laws mandating that up to one percent of the costs of

new city construction and renovation be spent on art), community muralists

began to compete for city projects.

This movement out of the neighborhoods and into the mainstream corresponded

to the increasing professionalism of muralism, and the desire of artists

to have the opportunity to create major and permanent works. In Los

Angeles, this process was more successful than in most other cities,

helping to make it the "Mural Capital of the World." During the 1984

Olympic Games, ten of the established community muralists--Chicano,

black, and white--were commissioned to paint murals on downtown freeway

walls, thereby bringing the murals to the attention of middle-class

residents and visitors from around the world--most of whom would never

travel into the neighborhoods where the early masterpieces had been

painted. Murals became one of the tourist attractions of the city, a

source of "neighborhood pride," and a deterrent to graffiti and gang

violence. As such, they continued to receive substantial funds and support,

even as the recession of the late 1980s forced cutbacks in cultural

funds in many other cities.

In the twenty-five years since the heyday of the Chicano movement,

the melting pot analogy of American society has given way to a "salad

bar-style" celebration of multicultural diversity. Concurrently, the

art world has gone from favoring minimalism and hard-edge abstraction

to espousing postmodern eclecticism with exhibitions of gender, identity,

and politics. The once revolutionary idea that community residents should

have some say about the art placed in their neighborhood has become

incorporated into the selection process of almost all public art programs.

Finally, some community artists are receiving a share of the large commissions

that make possible really major works and larger audiences.

The trajectory of murals from the barrio to the mainstream is exemplified

in the career of the East Los Streetscapers, a group that formed in

the early years of the mural movement. In 1973, David Botello painted

his first mural, Dreams of Flight, at Estrada Courts, and a year later

Wayne Healy (who happens to be half-Irish and half-Mexican) painted

Ghosts of the Barrio at Ramona Gardens. The two men joined together

in 1975 to form the Streetscapers group, and they continue their collaboration

to this day.7 Together, they painted Chicano Time Trip in East L.A.

in 1977. All of the above mentioned murals are considered to be classics

of the early Chicano movement, presenting a positive message to young

people regarding their cultural heritage. Botello and Healy painted

new walls almost every year, both in the barrio and in mixed neighborhoods,

while holding down other jobs to support their families. In addition

to Chicano themes, they created a 500-foot-long space odyssey, Moonscapes,

for the Culver City branch of the California Bureau of Motor Vehicles

building, and an 80-foot-high mural, El Nuevo Fuego, on the Victor Clothing

Company building in downtown, which debuted during the Olympics. In

1990 they founded the Palmetto Gallery, a work and exhibition space

for younger artists as well as for themselves. As experienced and respected

muralists from the community, they have been able to win a number of

art competitions for public commissions in the 1990s, including one

for a Metrorail station and another, ironically, for a police training

facility. This is a long way from the politically motivated early walls

or the calls to struggle of the Irish militants. Is it a contradiction

or a progression?

The situation certainly contradicts the romantic image of a politically

motivated mural movement--something that has not existed for some fifteen

years. However, success and professionalism by themselves need not be

interpreted as a sellout of the movement, as long as commitment to the

community continues. Each work must be judged individually by the integrity

of its content, not just by the identity of the patron; after all, Rivera

painted some of his greatest murals for major capitalists like Ford

and Rockefeller. Moreover, only through more accessible and permanent

work that demonstrates a complexity of thematic material and a high

level of artistry can a mural phenomenon be transformed into a continuing

art movement that has influence for more than a few years.

In spite of the mainstreaming of the community mural movement, positive

images of ethnic history remain controversial in a changing political

climate. The conservative backlash has promoted a growing intolerance

for opposing views and multiculturalism, as demonstrated in two recent

cases. Recently, objections were raised to a proposed Metrorail station

design by Margaret Garcia. The chosen location, near Universal Studios,

is also the historical site of Campo de Cahuenga, where General Pico

surrendered California to United States forces in 1847. Using text,

Mayan symbols, and images, Garcia's design recounts that history and

that of Native American and Mexican residents of early California. Objections

come from those who feel that this view of history negatively portrays

white Americans. The other case concerns more recent history. A mural

honoring the memory of the Black Panther Party, by Noni Olabisi, in

a black neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles (and originally funded

by city money through the SPARC Neighborhood Pride program) was denied

permission by the Cultural Affairs Commission after a series of stormy

hearings. This mural was painted, but with private rather than public

funds.

As they walk the thin line between banality and censorship, the muralists

of the United States continue on a path toward ever more ambitious artistic

expressions on the issues facing different communities today. In Ireland,

the republican muralists are now at a crossroads. They may stop painting

walls now that peace seems to be at hand--or they may change with the

times and, like the community muralists of the United States, convert

themselves into a continuing voice of the people.

Global Health, Los Angeles, 1991. Mural by East Los Streetscapers

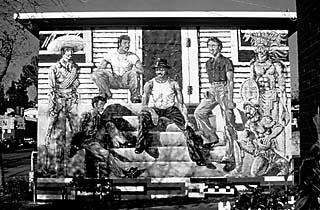

Ghosts of the Barrio, Los Angeles, 1974. Mural by Wayne Healy, East

Los Streetscapers

Maestrapeace (detail), San Francisco Women's Building, 18th Street,

San Francisco, 1994. Mural painted by Juan Alicia, Miranda Bergman,

Edythe Boone, Susan Kelk Cervantes, Meera Desai, Yvonne Littleton,

and Irene Perez. Photo by Bill Rolston

|