|

Introduction

There is widespread support for the view that many contemporary Irish

attitudes and behaviours have their origins in colonialism.2 However,

no comprehensive hypothesis exists to explain how this evolutionary

process might have taken place. This article attempts to integrate and

build on previous contributions to the field by using the trans-generational

model of parental child abuse to explicate how subjugated peoples (in

this case Irish Catholics) could be damaged psychologically by political

oppression (in this case British colonialism).

Children who are subjected to severe and prolonged abuse by parents

or other authorities tend to internalise the abuse in the form of a

behavioural syndrome characterised by pathological dependency, low self-esteem

and suppressed feelings which I have called 'malignant shame'. As adults,

shame-based children are likely to abuse their children in much the

same way as they themselves were abused by their parents, thus transmitting

the syndrome of malignant shame to the next generation. And so on down

the line.

Could a similar process exist at the cultural level whereby prolonged

political or governmental abuse of an entire population might be internalised

as malignant shame by the institutions of society, and transmitted unwittingly

to subsequent generations in the policies and conduct of government,

church, school and family?

There is reason to believe that such a cultural process has been endemic

in Ireland for many centuries, and that its destructive consequence

of malignant shame (low self-esteem, pathological dependency, self-misperceptions

of cultural inferiority and suppression of feelings) is a fundamental

cause of contemporary psychological, social, political and economic

distress in the country at this time.

Clinical experience with families suggests that a combination of psychological

and spiritual recovery is an effective treatment for malignant shame,

and also perhaps the only way to prevent it from being transmitted to

the next generation. If malignant shame should prove to be a significant

problem for Ireland at a national level, then a similar prescription

will undoubtedly be required, but on a much larger scale.

Background

In April of 1967 I was the Director of the Psychiatric Emergency Service

of the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. The riots following the

assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King were in full blast, and the

hospital, situated in the centre of a black poverty area, was in a virtual

state of siege.

The emergency room was crowded with casualties, some of them physically

wounded, others mentally distraught. Among this latter group were several

young black men who had been arrested for looting, drinking and 'running

amok'. As Psychiatrist-in-Charge, I made a policy decision not to accept

these individuals for treatment because I did not consider them to be

psychiatrically ill. Instead, I asked the police to bring in the young

men who were not looting and rioting, but staying at home behind closed

doors watching the riots on television.

My policy got me into a lot of trouble with the police and the hospital

authorities. They did not concur with my view that socially aggressive

behavior by young black men after the murder of Dr. King could be considered

a psychologically normal response given the long history of racism,

segregation and cultural abuse that blacks had endured in Baltimore

and other parts of the American South until that time. I wondered if

the young men and women who showed no external signs of anger were,

in fact, exhibiting signs of post-colonial stress disorder? Split off

from their experience of healthy rage by a pathological fear of expressing

feelings, were they unconsciously re-enacting the attitudes of passive

compliance traditionally expected of slaves and other oppressed peoples?

Post-Colonial Psychological Syndromes

Prominent Third World political writers such as Franz Fanon, Edward

Said and Albert Memmi have identified post-colonial dependency as a

major barrier to progress for de-colonised peoples. The core of the

problem for any post-colonial population is a widespread conviction

of cultural inferiority generated by prolonged abuse of power in the

relationship between coloniser and colonised. Concentration camp survivors,3

former cult members, liberated hostages and repatriated prisoners of

war similarily may be plagued in the aftermath of 'freedom' by a lifetime

of irrational emotions, especially shame and guilt.

Whether they know it or not, Irish Catholics all over the world have

inherited a history that evokes images of shame, oppression, deprivation

and bigotry. In spite of this, they have, as a group, become justly

known for their courage, wit, good humour and generosity, not to mention

their imagination, sense of higher purpose and legendary capacity to

triumph over adversity. These qualities have enabled them to attain

unprecedented distinction in business, law, medicine, politics, religion

and the arts.4 And yet many of them, even some of the most successful

ones, say that they struggle privately with chronic feelings of shame

and a painful sense of personal and cultural inferiority.

This discrepancy of feeling is certainly familiar to me. I grew up

as an Irish Catholic in a loving cultured Fine Gael family where political

discussions seemed to focus on the brutalities of the civil war, which

had ended only fourteen years before I was born, and in which my father

had served as a medical officer in the Free State Army. Little was said

in my hearing about the centuries of colonial history that had caused

the war, and my parent's sympathies lay with Britain in her struggle

against Hitler. At school, the Irish history I was taught included robbery

of our lands by plantations of English colonists, deliberate impoverishment

of Irish Catholics through the Penal Laws, and near-elimination of the

Irish peasantry by planned neglect and forced emigration during the

Famine. Despite this knowledge, I had by the age of eight developed

a conviction that England was a source of higher (and better) authority

on nearly all matters except Catholicism. In my early teens I came to

believe that everything Irish (including myself) was in some way defective

or second-rate in comparison to England.

By the time I left Ireland in 1960 to take up voluntary exile as a

psychiatrist in North America (where I have remained ever since), this

self-misperception of cultural and personal inferiority (which I would

later call malignant shame) had become the core of my identity; indeed,

it may have been the principal reason for my departure from Ireland,

although I wasn't aware of this at the time. Twenty years later, a divorce,

re-marriage, recovery from alcoholism and a serious bout with cancer

caused me to take stock of my personal situation.

In the mid-1970s I had been invited back to Ireland by Professor Ivor

Browne of Dublin to direct a series of Group Relations conferences on

unconscious aspects of authority and responsibility sponsored by the

Irish Foundation for Human Development. This opportunity brought me

into contact with Mr. Paddy Doherty and other Derry leaders working

to help their city survive the ravages of military occupation, guerilla

warfare and sectarian strife. While attempting to take full responsibility

for my personal problems and the damage they had caused me and others,

my exposure to the terrible consequences of imperialism in Northern

Ireland led me to wonder if the trans-generational dynamics of my family

of origin in Dublin and my family of choice in Los Angeles might not

also be a micro-cosmic reflection of colonialism. If this were so, then

the strengths and weaknesses of my own character could be seen as a

psychological legacy of the colonial process manifesting itself at an

individual as opposed to a cultural or community level.

A perusal of 20th-century Irish writing finds support for this view.

Many writers and historians have attributed self-misperceptions of personal

and cultural inferiority among Irish Catholics to the effects of British

colonialism on the national psyche. Professor Joseph Lee refers to the

'elusive but crucial psychological factors that inspired the instinct

of inferiority', and has identified self-deception, begrudgery, contempt

for authority, lack of self-confidence and poor leadership as post-colonial

behavioural constraints on the pursuit of productivity and happiness

in contemporary Ireland.

Dr. Anthony Clare, a prominent Irish psychiatrist, while emphasising

the 'extraordinary vigour and vitality of so much of Irish life', also

describes the Irish mind as being 'enveloped, and to an extent suffocated,

in an English mental embrace'. This development has occurred, he says,

in 'a culture [that is] heavily impregnated by an emphasis on physical

control, original sin, cultural inferiority and psychological defensiveness'.

The paradoxical and contradictory construction of the 'Irish Catholic

Character' is itself a clue to history. Humour, courage, loyalty and

tenderness co-exist with pessimism, envy, duplicity and spite. A strong

urge to resist authority is tempered by a stronger need to appease it.

A constant need for approval is frustrated by a chronic fear of judgment.

A deep devotion to suffering for its own sake is supported by a firm

belief in tragedy as a virtue.

Freud, Jung and other psychoanalytic theorists believed that individuals

are destined to act out apocalyptic themes of ancient history that are

handed down from generation to generation through the institutions of

society and in the collective unconscious. Thus, Irish Catholics might

have a tendency to re-enact in their daily lives the most degrading

themes of Irish colonial history, including the double tragedy of triumph

through failure or failure through triumph, each option providing a

painful, but safe, haven from ambition. In my experience, these destructive

re-enactments were most readily observed during struggles for political

power within families, and in the relationship between teachers and

pupils at school. Shaming strategies such as ridicule, teasing, contempt

and public humiliation are clearly rooted in the historical reality

of political oppression. Devious conniving, silence as a form of communication,

interpersonal treachery, and secret delight at the misfortunes of others

are contemporary reminders of the familial savagery and tribal betrayal

to which at least some of our forebears must have turned in order to

survive under colonial rule.

Alluding to the psychological impact of foreign and political domination

(of Irish Catholics) in Ireland, Clare points to the need for exploration

of the Irish penchant 'to say one thing and do another'. Wisely, he

warns that investigation of this topic and related issues will require

sensitivity and tact if defensiveness and the risk of feeding the Irish

tendency to self-denigration is to be avoided.

Nevertheless, the exploration must proceed. The short and long-term

effects of potentially destructive post-colonial influences on work

performance and human relationships in Ireland should be a matter of

national concern. The post-colonial mentality which, according to Lee,

impedes ambition and constrains progress by 'shrivel[ling] Irish perspectives

on Irish potential' must be identified and harnessed for positive purposes

if the current spiritual, cultural and economic renaissance in Ireland

is to continue, and the concomitant movement towards peace in Northern

Ireland is to be maintained.

Historical Background

This section and the one that follows contain a brief (and highly selective)

review of pertinent Irish history, a description of how and why shame-based

parents inflict emotional damage on their children, and an introduction

to the psychology of malignant shame. An awareness of how these issues

are linked will help the reader to identify the connection between family

abuse and political oppression. In turn, this awareness will clarify

how the oppressive relationship between coloniser and colonised in Ireland

has produced self-misperceptions of cultural inferiority (malignant

shame) in significant segments of the Irish Catholic population.

At various times since the reign of Elizabeth I, English governments

have justified oppression of Catholics in Ireland on the grounds that

the Irish were an inferior race and a shameful people.5 At the end of

the 17th century, the Penal Laws were enacted by the colonial govern-

ment specifically to impoverish and degrade Catholics in Ireland, and

to undermine or eliminate the influence of the Irish Catholic Church.

All Irish Catholic institutions which carried traditional values, attitudes

and religious beliefs were targeted for destruction. These draconian

laws were enforced, more or less, for about eighty years or until 1770,

when a process of repeal was initiated only because the repressive legislation

had achieved its original objective of 'preventing the further growth

of popery', and 'eliminating Catholic landownership'.6

Over centuries, the potential for tribal solidarity among Irish Catholics

was consistently undermined by land-rape, poverty, discrimination and

the readiness of the Crown to exploit the venality of Irish despair

through the purchase of treachery from paid informers. After the Act

of Union in 1801, and the failed insurrections of 1798 and 1803, the

spirit of Irish Catholicism was further weakened by the systematic elimination

of the Irish language as an essential cultural symbol. Even after Catholic

Emancipation was achieved in 1829, native Irish experience was increasingly

devalued, and preferred styles of dress, behaviour and thought were

defined in terms of the dominant British colonial culture.

Then came the Famine in 1845, and with it a real possibility of annihilation

or abandonment of Irish Catholics by disease, starvation or neglect

by the British government. 1.2 million people died in less than five

years, 2 million more emigrated to the U.S. during the next decade,

and by 1850 large parts of Ireland (particularly the West and Southwest)

must have resembled nothing more than a 600-year-old concentration camp.

Throughout this time and later, English newspapers and journals, most

notably The Times, Punch and The Illustrated London News generated powerful

denigrating stereotypes designed to promote the view that Irish Catholics

were at least partly responsible for the catastrophe that had befallen

them. Their laziness, stupidity and superstitious religious beliefs

were said to have brought on the Famine, which was conceptualised by

some politicians and churchmen as a just punishment from a wrathful

God for the sinful and rebellious attitudes of Irish Catholics. 'The

great evil with which we have to contend', wrote Charles Trevelyan in

1848, 'is not the physical evil of the famine but the moral evil of

the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people'. As Treasury

Secretary of the British government, Trevelyan was responsible for the

funding of Famine relief operations.

There is considerable evidence to suggest that Trevelyan's official

'British Government' attitude persists 150 years later as a powerful

dynamic of the current war in Northern Ireland. In an interview with

the Belfast Telegraph on May 10, 1969, Mr. Terence O'Neill made the

following statement after resigning as Northern Ireland Prime Minister:

It is frightfully hard to explain to Protestants that if you give

Roman Catholics a good job and a good house, they will live like Protestants,

because they will see neighbours with cars and television sets. They

will refuse to have eighteen children, but if a Roman Catholic is

jobless and lives in a most ghastly hovel, he will rear eighteen children

on National Assistance. If you treat Roman Catholics with due consideration

and kindness, they will live like Protestants in spite of the authoritative

nature of their Church.

Other pertinent 19th-century literary extracts include the following

well-known and widely cited quotations. The first of these was penned

by Charles Kingsley, author of The Water Babies and other classic English

novels, in a letter to his wife after a brief tour of Ireland in 1860:

I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles

of horrible country. I believe that there are not only many more of

them than of old, but that they are happier, better and more comfortably

fed and lodged under our rule than they ever were. But to see white

chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black, one would not feel it

so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as

white as ours.7

In an 1862 article entitled 'The Missing Link', Punch had this to say

about immigrant Irish labourers in England:

A creature manifestly between the Gorilla and the Negro is to be

met with in some of the lowest districts of London and Liverpool by

adventurous explorers. It comes from Ireland, whence it has contrived

to migrate: it belongs in fact to a tribe of Irish savages: the lowest

species of the Irish Yahoo. When conversing with its kind it talks

a sort of gibberish. It is, moreover, a climbing animal and may sometimes

be seen ascending a ladder laden with a hod of bricks.

From a historical perspective, however, the British government cannot

be held solely responsible for the distress of the Catholic population

in Ireland then and now. By a peculiar quirk of historical irony, the

19th-century Irish Catholic Church and its faithful adherents may also

have contributed to the process as they struggled together to recover

from centuries of persecution and near-annihilation at the hands of

the English.

By 1850, substantial numbers of Irish Catholics, separated from their

lands, devastated by starvation and disease and apparently deserted

by government during the Famine, had come to believe that human misery

was all they deserved and all they could expect from their colonial

masters. Naturally, they looked to the Catholic Church for succour and

salvation. The Church's response was immediate, powerful and above all

successful, because it stopped a potentially genocidal process from

gaining a fatal momentum. But the psychological and spiritual price

of survival was high; so high, in fact, that it is still being paid

150 years later by significant numbers of Catholics in Ireland, and

by many more on the diaspora, including myself.

Survival of the Church and the Evolution of 19th-Century Catholicism

As part of its survival strategy in the early part of the 19th century,

the Irish Catholic Church, having been persecuted, shamed and humiliated

by the British government for almost one hundred years, now joined forces

with it to suppress the insurgence of militant nationalism in Ireland.

This unhappy but efficient alliance led the Church to internalize unconsciously

the most abusive aspects of Anglo-Irish history and the Victorian culture,

including suppression of feelings, repression of sexuality and the devaluation

of women's and children's rights. These negative social values were

reinforced by a devotional revolution which emphasised sexist elements

of Augustinian and Jansenistic theology imported from France and, ironically,

incorporated a strict practicum of religious rituals borrowed from England,

including Novenas and the Rosary. In the latter half of the century,

the ordinary people of Ireland clung to their religion as a badge of

identity and a weapon of defiance. For many, Catholicism became a substitute

nationality, and nationalism a form of secular religion.8

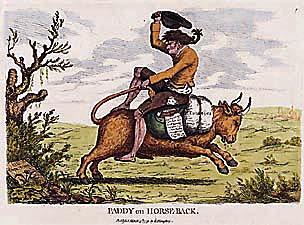

W. Humphrey, Paddy on Horseback, 1779

Emigration

Although emigration by Catholics and Protestants from Ireland to the

U.S. and elsewhere had been common since the middle of the 17th century,

an enormous exodus of Catholics to North America began in 1847, the

peak year of the Famine. Lacking material goods to take on the Atlantic

journey, the emigrants brought with them instead the austere, authoritarian

survival ideology of 19th-century Irish Catholicism, as well as the

usual colonial stigmata of second-class citizenship and low self-esteem.

What awaited many of these immigrants in the land of promise was poverty

worse than anything they had known in Ireland, and an impenetrable wall

of racial prejudice and religious discrimination:

Woman wanted to do general housework--English, Scotch, Welsh, German

or any country or color except Irish.9

Again, the Catholic Church came to the rescue. Irish clergy, in their

traditional role as cultural defenders of a devastated people, used

strong infusions of vigourous faith and national pride to counter the

racism and bigotry aimed at their immigrant flock.

The parish became more important than the neighbourhood, and the priests

demanded total obedience to their rule. This clerical strategy helped

the immigrants to gain a firm toe-hold in the New World by imbuing them

with hope and a strong sense of community. It also positioned them to

use their native survival skills to the best advantage in the astonishing

ascent that would soon bring Irish Catholics to the pinnacles of material

success and political power in the U.S.10

Meanwhile, back in Ireland, the 19th-century survival strategy of the

Catholic Church to suppress both affect and insurrection was a brilliant

success, but at what price? According to Monica McGoldrick, the Church

consolidated its control of the people (and thereby ensured its own

survival) 'by holding the key to salvation in a land where this life

offered so little'.11 After 1850, the Church may have unwittingly passed

on the essentials of its survival plan to subsequent generations of

Irish Catholics. Shame, guilt, terror and celibate self-sacrifice were

key elements in the Church's campaign to deal with the critical problems

of over-population, land shortage and the patronymic system of inheritance.

Original sin, sexual repression and eternal damnation were incorporated

into a grim theology of fear that led Irish Catholics to believe they

had been born bad, were inclined toward evil and deserved punishment

for their sins.11 This bleak spiritual philosophy, which evolved in

the harsh climate of famine and colonialism, would later become the

foundation for 20th-century Irish Catholicism and has remained so to

this day, despite the changes of Vatican II and the many departures

from tradition by courageous clergy at every level of Church organisation.

Cartoon, 1867. National Library of Ireland

Two Varieties of Shame--Healthy and Malignant

In order to highlight the dynamic similarities between parental abuse

of children and political oppression of populations, the foregoing account

deliberately juxtaposes the abusive aspects of Irish history with the

extraordinary ability of the people to overcome them. Similarly, the

coping skills developed by children to survive familial abuse can become

the principal tools of their achievement as adults. As we shall see,

however, the price that many children of abuse pay for their later material

or professional success is to be isolated from their authentic feelings

by malignant shame, and therefore to be rendered incapable of achieving

intimacy in relationships. The implications of a similar outcome for

an entire population would be devastating.

Physiological or healthy shame is a critically important motivating

factor in the psychology of learning and character development. Healthy

shame enables children to grow in two ways. First, it helps them to

identify the limit of their ability, and then impels them to exceed

it. However, like anxiety and guilt, which, in the 'right amounts' are

essential for our psychological well-being, healthy shame can become

pathological or malignant under certain circumstances.

Healthy shame becomes malignant when it ceases to motivate behaviour

that is consistent with normal growth and development, but instead is

used as a weapon by individuals or groups in authority to control or

manipulate the actions and attitudes of those under their power. For

example, insecure parents may shame and punish their children into submission

for the same behaviours or inadequacies that they are unable to tolerate

in themselves. Authority figures in schools, prisons, churches and the

military can, and do, perpetrate verbal, physical, sexual and religious

abuse on their charges in the same manner and for the same reasons.

Calculating politicians have used shame in their attempts to break the

spirit of entire peoples as they did when subjugating the Native Americans,

when murdering the Jews and when neglecting the Irish Catholic peasantry

during the Great Famine.

Malignant shame, more than a simple emotion, is an identity: a more

or less permanent state of low self-esteem that causes even successful

persons to experience themselves as being unworthy, and to view their

lives as being empty and unfulfilled. No matter how much good they do,

they are never good enough. Shame-based individuals may experience themselves

privately as objects of disgust, feel secretly flawed and defective

as persons and live in constant fear of being exposed as stupid, ignorant

or incompetent.

Malignant shame is a psychological survival mechanism which makes it

difficult or impossible for abused persons to express their feelings

of anger and rage, because to do so would place them at risk for further

damage through retaliation by the perpetrator. Thus, abuse victims often

remain passive in the face of punishment because they suspect that the

rage and criticism of their perpetrator is both accurate and justified.

In extreme cases, severely abused children or battered wives may come

to experience verbal, physical or sexual abuse from their parents or

husbands not as a form of assault, but as an expression of love. Malignant

shame is an important element of the protective dynamic that causes

hostages to revere their captors, prostitutes to love their pimps, revolutionaries

to admire their oppressors and 'the Irish to imitate the English in

all things, while apparently hating them at the same time!'.12

Reduced or absent self-esteem may cause children of abuse to create

false personas or caricatures of themselves to divert attention away

from what they believe to be the hateful, shameful truth of their 'real'

identities. Such children are, quite literally, 'not themselves'. Having

lost touch with both their authenticity and their feelings, they may,

as adults, become inordinately dependent on the approval and judgment

of others for estimations of self-worth.

An Irish settler in New York, 1850s. Cartoon by Thomas Nast; courtesy

of Culver Pictures Inc., New York

Discussion

When viewed side by side, the historical evolution of Irish Catholicism

and the trans-generational dynamics of parental child abuse would appear

to have certain features in common. Oppressed nations and abused children

may suffer more than their share of unnecessary pain in the process

of growing up. Both will experience problems with authority, dependency,

identity and entitlement, and both will be compromised in their ability

to integrate thought, feeling, intellect and action in such a way as

to promote intimacy and facilitate growth.

Like the child of an abused parent, the 19th-century Irish Catholic

Church may have internalised a core identity of malignant shame as a

response to generations of persecution by the British Government under

the Penal Laws. In keeping with the psychological imperative that seems

to mandate the trans-generational transmission of unacknowledged shame,

the harsh and punitive spiritual pedagogy to which the Church bound

its adherents at mid-century may have been as much a vehicle for the

unconscious transfer of the Church's malignant shame to the next generation,

as it was a pragmatic and effective social strategy to avert the real

possibility of abandonment or annihilation of poor Catholics during

and after the Famine. In the same way that the caricature or false persona

of an abused child can be regarded as a behavioural adaptation to the

threat of parental abuse, the 'Irish Catholic Character' can perhaps

best be seen as a caricature of itself, a cultural false persona based

on massive misperceptions of inferiority which evolved as a survival

mechanism in the struggle against prolonged abuse by British governments

and their representatives in Ireland.

In 1992 I presented an early version of this paper to a largely Catholic

audience in Derry. Some were angry, others were stunned, but many could

identify. After the lecture, certain members of the audience challenged

my authority to speak on the grounds that I had left Ireland thirty

years previously and "no longer had my finger on the pulse of the nation".

I had no right, they said, to be "putting the Irish down or accusing

them of mental illness" when support and encouragement was what was

needed "after all [they] had been through". Protestations by me that

I was proud to be Irish, loved my country and still went to Mass and

Communion occasionally seemed only to inflame a significant segment

of the audience, some of whom adopted a rather threatening stance. At

a point when the discussion seemed likely to take a nasty turn, a prominent

local physician cried out "Stop! O'Connor is not the problem. The real

problem is what do we do with our anger?" "And how about our tenderness?"

said a woman quietly in the sudden silence that followed his remark.

Both of them were right. The most crippling feature of post- colonial

cultural malignant shame in Ireland is an unconscious collusion between

the people, the Church and the government to suppress socially significant

expressions of intimacy and rage by obliterating them with shame, trivialising

them with ridicule or condemning them with diatribes of moral indignation.

The implications of this kind of censorship for personal growth, institutional

development and the recovery of indigenous pride in a post-colonial

environment are profound because human beings, when isolated from their

feelings, are also cut off from their humanity, which, in turn, makes

them prone to self-pity and compulsive victimhood. Plantation of this

evil partition in the mind of the people was, and is, one of the most

destructive consequences of British colonial policy in Ireland, because

it fosters the development of pathological dependency, strongly supports

a culture of blame and actively impedes the process of emotional liberation

which is vital for sustained self-appraisal. "If you don't know how

you feel, you don't know who you are. If you don't know who you are,

you are probably leading somebody else's life!".

The split between thought and feeling is evident at every level of

Irish life. While we Irish are celebrated for being willing to display

our emotions through fictional characters in poetry, drama, literature

and song, we are not very skilled at revealing our true feelings in

the intimate narrows of face-to-face relationships. At home, many of

us are reluctant to speak to each other about our private yearnings

for affection because expressions of feeling or physical contact are

usually discouraged in families--although compulsive talking to ourselves

or others is readily accepted on account of its unique capacity to stifle

emotion.

In the absence of formal research which has yet to be conducted, the

arguments presented in this paper are based on my clinical observations

of malignant shame in hundreds of patients, and my experience of the

phenomenon as a self-destructive influence in my own life. The positive

response I have received from trusted friends and colleagues with whom

I have shared these preliminary ideas has encouraged me to think more

about how I internalised my cultural malignant shame through interactions

with my family, school, church and government, and how I have passed

it on to my children and others dear to me through various abuses of

power and authority on my part. A better grasp of the process which

facilitated this transmission in my case might prove to be helpful for

larger numbers of people struggling with the same issues.

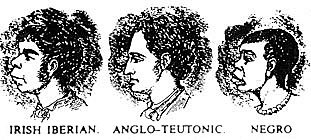

Scientific Racism as depicted in Harper's Weekly, 1898

Despite a public record of some small professional accomplishment in

my life, I continue to struggle privately with many of the conflicts

described in this article, especially those related to authority, identity,

entitlement and judgment. Over the years I have come to understand my

behaviour in these areas as a disorder of belonging--a post-colonial

character syndrome manifested intermittently by procrastination, ambivalence

about aggression, magical thinking and difficulty with intimacy in my

most cherished relationships. In my case at least, the common denominator

of these personality characteristics is an irrational need for approval

by others and a simultaneous fear of their negative judgment.

The roots of this syndrome can be traced to my relationships with parents

and siblings at home, to my interactions with Holy Ghost fathers and

Jesuit priests at school, to my early but instinctive tendency to delegate

higher authority to British values, institutions and objects, and finally

to vivid and terrifying childhood images of my personal and public vilification

by God on the day of the Last Judgment. Many years of 12-Step work combined

with personal psychotherapy have given me a set of psychological tools

to deal with these problems. However, the spiritual dimensions of my

recovery did not come into focus until I became willing to consider

my personal development in terms of my cultural history, and to discern

a pattern of connectedness that embraced the diverse and often contradictory

elements of my national identity.

The argument has been put to me that conflicts of authority, identity

and entitlement can occur independently of culture and should not, therefore,

be attributed to the influence of any particular political system. While

it is certainly true that such conflicts are universal and ubiquitous

in human experience, they appear to be concentrated in post-colonial

cultures such as Ireland and Mexico where imperialistic forces have

subjected the indigenous populations to appalling excesses of political

abuse and unnecessary suffering over many generations. I have been told

in no uncertain terms that my proclivity as a physician to talk publicly

about my personal experience with these conflicts is both inappropriate

and embarrassing. Instead, I have been advised to confront my cultural

demons by disguising them as fictional characters in a novel, or by

having them evaluated in the privacy of a psychiatrist's office for

a possible trial of medications. After I mentioned in a public lecture

given at Dublin's Peacock Theatre in 1992 that my heroic and marvelous

mother was an alcoholic, a member of my family suggested quite seriously

that I should cease my cultural researches to pursue other work opportunities.

In other words, I should keep quiet.

That is my point. I believe that the post-colonial syndrome of malignant

shame has caused many of us in the Irish Catholic community to be ashamed

of being ashamed, and therefore to conceal or remain silent about the

healthy shame which is our life-line to integrity, ambition, power and

success. The real 'hidden Ireland' lies buried in the malignant shame

of each individual and each institution in the country, and indeed in

every Irish person throughout the world regardless of religious affiliation.

But it is we Catholics who must ultimately take leadership to break

the silence about the hidden shame of being Irish, and to bring it,

and ourselves, out of personal hiding. It is hard to know how to proceed

with this process of externalisation, because factors such as embarrassment

and concern for the sensibilities of others must always be considered.

But there is no alternative, in my opinion. Finding ways to share our

'experience, strength and hope' is an essential first step in resisting

the seduction of false pride which is the emotional hallmark of the

true victim. Failure to act will sentence too many of us to a shame-based

future as dedicated blamers, whiners and Pollyannas who will surely

pass our unresolved social issues and family conflicts onto the children

of our next generation.

Even though the current peace process in Northern Ireland may soon

result in the departure of British troops from the six counties, the

occupation of the Irish mind by psychological relics of colonialism,

including malignant shame and the capacity for self-deceit contained

in the national tendency to say one thing and do another, will continue

indefinitely. Although malignant shame is differentially distributed

in the Irish Catholic population (that is, some people and some institutions

have more of it than others), the incidence of shame-based conditions

such as alcoholism, depression, suicide, child abuse, ruined marriages

and unfulfilled dreams is paradoxically elevated in Ireland where loyalty

to family, love of children and respect for the dignity of life are

also highly valued. Institutional undercurrents of malignant shame are

suggested by the contemporary tragedies of the Kerry babies, Miss 'X',

Bishop Casey and the pedophiliac scandals in the Irish Catholic Church.

Potential candidates for analysis from a historical perspective of cultural

inferiority and malignant shame might include the conduct of the plenipotentiaries

during the Treaty Talks of 1921 and the role of 'cultural drinking'

in the death of Michael Collins.

Perhaps the target of the next guerilla war in Ireland should be the

negative attitudes and value judgments about ourselves that are rooted

in a combination of denigrating colonial stereotypes and anachronistic

19th- century Irish Catholic dogma. Deep rivers of dammed-up anger are

waiting to be released at every level of society, and the dishonest

practice of condemning revolutionary violence in public while supporting

it in private should be discouraged through promotion of a communications

climate in which individuals can feel free to express their authentic

feelings and opinions without the risk of being condemned as terrorists.

Two Faces (detail), by Sir John Tenniel, 1881, published in Punch

It is likely that the majority of people reading this article will

find its thesis to be neither plausible nor palatable, coming as it

does from a person who has lived in exile for thirty-five years. They

may argue that 'all that is behind us' and that 'to focus on it now'

may endanger the momentum of disengagement from Britain that has begun

with Ireland's shift of trade emphasis to the European Community. I

contend that 'all that is ahead of us'. We should know that malignant

shame is a permanent element of the colonial legacy which will accompany

us wherever we go, and which will continue to exert its evil influence

on the people and institutions of Ireland unless some formal effort

is made to identify and confront it at a national level. There needs

to be a clear understanding and acceptance of the fact that all institutions

and traditions of Irish society have been traumatised by imperialism,

and that remedial action must therefore include South as well as North,

Protestant as well as Catholic and so on through all the diversities.

Our willingness as Catholics and Protestants to abandon our respective

roles as living caricatures of a narrow and hostile cultural stereotype

would give us the courage to speak to ourselves and to our future as

a nation of triumphant mongrels who have proudly integrated the shame

and the power and the love of our rich and rare polycultural past.

Formal adoption of a perspective which emphasises the need for individual,

family, institutional and community recovery from colonial trauma should

include the creation of psychological and cultural institutions to serve

as active containers for the outpouring of suppressed and prohibited

feelings that will inevitably occur in the process of reconciling political,

personal, religious and class differences in Ireland. The availability

of such institutions would permit us all to take a part in the process

of healing the malignant shame that is tearing us apart because we don't

realise, or cannot accept, that it is a part of us. The Centre for Creative

Communications, soon to be established by the North West Centre for

Learning and Development in Derry, is an example of an institution that

has incorporated these vital purposes into its primary task.

In the meantime, perhaps the best prescription for Irish Catholics

in Ireland or anywhere else at this particular time would be that given

by Nelson Mandela to his own people in his inaugural speech as President

of South Africa in May 1994:

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate.

Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure.

It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us.

We ask ourselves, who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous,

talented and fabulous?

Actually, who are you not to be?

You are a child of God.

Your playing small doesn't serve the world.

There's nothing enlightened about shrinking so that

other people won't feel insecure around you.

We were born to manifest the glory of God that is

within us.

It's not just in some of us; it's in everyone.

And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously

give other people permission to do the same.

As we are liberated from our own fear,

our presence automatically liberates others.

American Gold (detail), by F. Opper, 1882

|