"What is the meaning of one fish?"

***

|

© Pedro Meyer, 2004

|

|

I don't know what the story is of this single fish, other than it seemed to be quite important to these men at the fish market in old Dhaka. Given that I do not speak Bangla, there was no way of finding out what the context was. This is of course the beauty and the limitation of photography, that it is open to any interpretation we wish an image to contain. So rather than speculate endlessly about the real meaning behind what we are looking at in this picture, I have decided to appropriate for myself it's meaning. It's about notions on the meaning of wealth. How rich is a man with one fish?

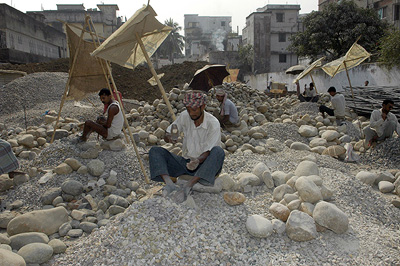

© Pedro Meyer, 2004 Bangladesh is according to economists, one of the poorest countries in the world. And of course the wages paid in the realm of one dollar a day, for breaking stones, or two dollars a day for pulling a Rickshaw all day long with a huge weight that many times is considerably larger than the individuals themselves, goes a considerable way in confirming that the announced levels of poverty in Bangladesh are no exaggeration.

© Pedro Meyer, 2004

© Pedro Meyer, 2004 However, statistics tend to also obscure other aspects of life that seem to get lost in such descriptions as "among the poorest in the world". I found that the people in Bangladesh are among the friendliest I have ever met any place, nothing to say that they must be the biggest enthusiast of having their picture taken that exists on the face of this earth. I did not find a single instance of someone not wanting their picture taken, what's more, I had a hard time making any pictures as no sooner did I point my camera in any one direction that I would find myself surrounded by dozens of eager candidates to have their image become part of the intended photograph. To capture some degree of spontaneity I had to act really fast. That is, before the crowd moved in and wanted to join the picture.

© Pedro Meyer, 2004 I have of course no desire to romanticize poverty, nor to turn away from the reality of their hard existence. Yet it is also very narrow minded to just look at poverty in comparison to any western standard of living. How does one factor in to such evaluations, when you also find that the ability for people to get along with each other, that is considerably better than many of those in west? My little son, when he was in his first years in school, was taught what was called: Conflict Management. The kids had to learn what to do and how to resolve conflicts, which of course are part of our daily living. Those skills seemed to be something that needed to be taught in school. Here in Bangladesh, I have the impression that this is something they acquire in the water that they drink, or something of the sort, as their attitudes of dealing with conflict in a positive manner is something that is so widespread among the population that surely they did not get such skills in any school program. Take a case in point, when there is a collision of rickshaws with other moving vehicles, the first topic they deal with is how can they fix the problem, not who is to blame. In almost all of the west, the first thing is establishing blame. Obviously in a society of the "have not", to resolve the problem at hand is more beneficial than to fix blame, as from the latter there is nothing much to be gained. In the west, the economic pursuit behind establishing who is at fault, is the more important matter. Probably the most efficient way of getting on with life is, how it is dealt with, in this very poor nation. The issue of how people look at pictures takes on another twist when I heard a story by Shahidul Alam, the man responsible for Chobi Mela III, (Chobi= photo, and Mela= festival, in Bangla) and the reason I find myself here in Dhaka. During an exhibition that was organized here. There was a work shop conducted some time ago, and the students work was displayed on the panels and presented to the community where the images were taken from. One of the girls in the audience, brought her goat to the exhibition, because she was pictured in one of the images, and she wanted to have the goat view the picture as well given that the goat was also in the picture. I doubt very much that in much of the west, the notion to bring a goat to a photographic exhibition to see it's image would be something that would occur to many of us. So there are indeed many things that one can learn in the context of an environment that has so many different ways of looking at photography.

by Shahidul Alam © 1991 This event here, is one of the largest of it's kind in Asia. Bringing photographers and their work to the forefront during the two weeks of this festival. I have met photographers from all over the region, and I am sure that as this festival grows over the coming years, Bangladesh will increasingly become a major center for the development of photography. And what better place to have such an event than a city, where to such a large extent, photography is welcomed by the population. Here again, the often mentioned statement about poverty and digital technology being incompatible is brought to screeching halt. I was able to print an entire exhibition here in Dhaka, with Epson providing the printers and papers, and it all working perfectly well. Rather than shipping prints and frames all over the world and going through all the usual problems of customs and the inherent costs of shipping and crating, we were able to circumvent it all by printing the show on site, the frames were all made in 48 hours ( and what beautiful frames, on top of it all), the exhibition opened in time. Another exhibition, which was going to go up parallel to mine, and sent from the USA, never made it out of customs. If anyone has doubts how you could be dealing with international exhibitions with more options than in the past, we can provide you with some interesting feedback. I have written many times in other editorials about safety and street photography, well here in Dhaka, as in any other large metropolitan conglomerates, there must be a number of "bad characters" as well, it's only that I have fortunately not run in to them, or that I do not attract them, either way, the thing is that I would never dare run around Mexico City, with the same degree of confidence that I found here. I am not the only one with such a sensation of feeling comfortable walking around with cameras around your neck in old Dhaka, however there was one photographer from Malaysia who seemed to have run into trouble every time he went out. So the question is, does one attract such problems or run ins while photographing on the street? Are some photographers, trouble magnets by their behavior? I wonder, and if so, I suspect that dealing with cultural differences is one of those things that photographers the world over need to have included in school programs were photography is taught. I do not know of a single school anywhere, that teaches such important matters to photographers. It is assumed that we know how to deal with such matters, and the truth is that it is not. As the year comes to a close, I am invaded by a degree of sadness, not only for all the great photographers that are no longer with us who died during this past year, but also about the political winds that seemed to have prevailed against all odds, at least so in the short run. Yet in spite of all of this, what keeps our spirits high is that that creators of art through out the entire world seem to be on the upswing. The intensity and dedication of artists throughout the world ( yes, I view photographers as artists and artists as photographers when they use photography) is thriving in spite of material limitations that appear to be part of the global landscape. It appears that having only one little fish is not such a terrible alternative when you know what to do and what to say. I get the feeling that there are more and more photographers who have this very clear. We wish you the very best for the coming year of 2005.

Pedro Meyer As always please joins us with your comments in our forums.

picture of exhibition by Shahidul Alam © 1991

|

|