The magnificent work of Seydou Keita first

came to my attention when a friend in Paris, Dominique Anginot, was

good enough to send me the CD ROM he had produced with Mr. Keita's

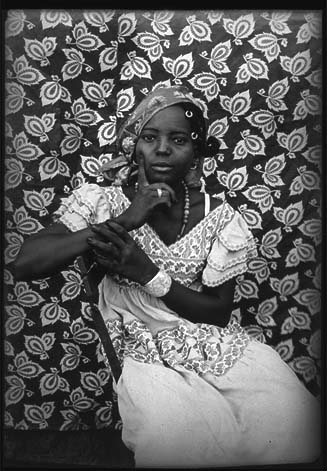

work. An excerpt of this splendid work done in Bamako, Mali, is

presented here with permission from Lux Modernis, the publishers of

this work.

I started to photograph in 1945 in BAMAKO. I am self taught; I had a 6x9 camera that one of my uncles had brought me back from Senegal. He had given to me also money to buy film. It all started like that. Honestly, it's a craft that I practiced the better that I could : I was really in love with photography.

At the beginning I photographed my family. Some attitudes worked, some others not. I really had a bad start : people moved and I probably trembled myself. When printing, they all looked like skeletons. You see : I was really undertrained. I was asking my client the money for the print that I was doing at Pierre Garnier's or at Mountaga's lab. He taught me how to print. If the print didn't come out well, I was into problems; clients were very angry, but they were the ones that moved!

In 1948 Mountaga admitted that I was qualified enough to lend me over his darkroom. I was doing all the processing, but in black and white only. Colour was around of course, but you had to send the films to France and anyway, I didn't like it. For me it was the black and white that was the right thing. In those days, there were 4 photographers in BAMAKO : Issouf, Boundyana, Mountaga and myself. Malik Sidibe came afterwards. We were all doing portraits, but people used to say that my "cards" were the best. I had a stamp that I put on all my prints.

In 1949, I bought a view camera and started with 5x7 negatives. I was doing contact prints, that's why I prefered 5x7. I had pinned on the walls of the studio various samples of my work : men or women in bust, alone or by two, or even groups up to 6 people, families and so on. The clients were telling me : we want to be photographed like this, you see? And I was doing it. But sometimes I was changing for a position that looked better. I was the one to decide in the last and I was never mistaking. It took only a few minutes, I shot one negative, never more. Many people were coming, buy on Saturdays, it was crowded: people were queueing: all sorts: shopkeepers, office clerks; even the president of the Republic came. I was doing the printing overnight and the spotting in the morning just before the clients would come and pick up their portrait.

With the 5x7 camera, the first backdrop that I used has been my bed cover. After, I changed them every two/ three years or so. That's how now I can know the dates of the images. Sometimes the backround worked really well with the clothes, specially for women's. But it was sheer luck.

In those days, the culture of the ancestors was not so strong as it used to be. City dwellers dressed up like europeans, very influenced by the french behavior. But not many people could afford to dress like that. At the studio, I had three different european suits with tie, shirt, shoes, hat, as well as some accessories : fountain pen, plastic flowers, radio set or telephone that I lent to customers.

For ladies, the dresses had not deeply changed yet. Western garments like skirts have been in fashion only in the late sixties. Women would come with their large dress and I arranged it: the more it was spread, the happier they were. The outfits had to show out in the picture: jewels were important as well as hands, long thin fingers, women were very concerned by that, they were signs of elegance and beauty.

I never met any foreign photographer. I never went out and I didn't know their photographs as well. One could not find here any french or american magazines. The only publication available was the Manufrance catalogue.

I was working just as well with natural light as with artificial light.Some customers would prefer "night photographs" because they were paler, but I preferred natural light. They really liked my photographs because they were really sharp and also because they appreciated their set up. All that I know is: my pictures were really good.

When I look at them today, they have not changed a bit, they didn't even change in color. I always worked with the same camera until 1977 and I kept all the negatives: they are all here: customers could reorder! None ever complained, otherwise they would have not returned.

If you like my work, you've got to know why. I know that many of my photographs are excellent and that's why you like them. I stopped photographing when color photography took over. People like it now but machines are doing the work. Many people call themselves photographers nowadays, but they don't know anything.

Françoise HUGUIER is a

photographer and curator

of the Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine.

One morning, in Bamako, I had to get my camera fixed, so I went to Malik Sidibe's camera repair shop. Malik Sidibe is a very skilled technician but in the 70's he used to be a photographer himself.

Of course, we talked about photography and he told me that a long time ago there was in BAMAKO a very famous portrait studio run by Seydou Keita.

Seydou Keita had stopped working but - what was very rare for Africa - he had kept all his archives.

The next morning I rushed to Seydou Keita's and the first thing that struck me was that all his work was neatly packed in labelled boxes: photos in feet, men, women; photos in bust, men, womenŠ

Of course there were neither prints nor contact sheets, nor proofs; I could only browse through negatives, hundreds of 5x7 negativesŠ

And it's the whole memory of a long gone era, the whole life of a BAMAKO's precinct that was awaiting there, in these boxes, and that was suddenly revealed.

But besides this patrimonial treasure I have been deeply moved by the images themselves. They were showing an exquisite sense of gesture, a skillfull art in posing the models, enhancing the outfits, the accessories.

As a photographer, I think that when you want to take someone's portrait the most difficult thing is to animate your subject and Seydou Keita does that perfectly, specially considering it's commercial work.

Framing for him is not a concern, he is not a photographer that cuts in reality, he is more a photographer that composes a representation.

The light in Seydou Keita's work is the one of Mali, the very pure light of Sahel. He uses to emphasize naturally the fleshtones, the garments, the jewelsŠ

He has a deep intimacy with his subjects, and I think that it partly comes from a traditional behaviour of the Malian community called "clientism" or "joking cousins".

But in fact, I think that in his photographs and even more of course in the women's portraits, one can guess that Seydou Keita was in love with his subjects. It shows.

DOMINIQUE ANGINOT

Lux Modernis

Communications Multimedia

4, Cite Griset, 75011, PARIS

+33 (1) 4923 7030

Luxmo@Dialup.Francenet.fr

|

|

|

|