|

|

ESPAÑOL | ||

|

WATSONVILLE, CA.

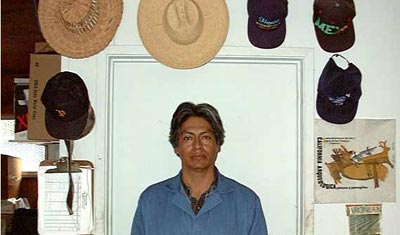

Miguel Ramos fits the bill of Migrant Makes American Dream, although his vision of that dream is radically different than Reyna Guzman's. Were the twain ever to meet, surely a brawl would ensue. Reyna is a heroine of the Watsonville Left; Miguel has recently acheived notoriety as a living symbol, for the United Farm Workers, of the "evil patrón." A lawsuit brought by the union claims that Ramos and his family organized and funded the Agricutlural Workers Committee, a group of anti-union workers, and thus broke U.S. labor law. He denies the charges. All this came as a shock to Joe and I. We'd met Miguel and his brothers, Juan and Antonio, last year when we first visited Watsonville, following the path of the Chávez brothers on their fateful journey from Cherán. We found conditions at Ramos Farms among the best we'd ever seen: clean toilets, morning, lunch and afternoon breaks dutifully observed, wages fairly distributed, nary a complaint from the workers. We also found morale among the work crew to be quite high. Florentino and Fernando Chávez, the surviving brothers, told us often of their patrón's generosity: loaning money for travel to the U.S., securing housing for them. A native of San Luis de la Paz, Guanajuato, Miguel came to Watsonville in the late 60s and began at the bottom, picking strawberries. Today, he is the patrón of Ramos Farms, a few dozen acres of strawberry fields, worked by about 50 field hands, mostly from Michoacán. At 42 years old, Miguel is a tall, striking man, with a shock of peppery hair parted in the middle over a handsome bronze face, an Indian face of almond-shaped eyes, blunt nose, and full lips. He wears a succession of faded, dirty baseball caps and, occasionally, a sweat-stained straw hat, the kind worn by poor tenant farmers in Mexico. He is almost always dressed in blue overalls, the kind auto mechanics wear. He often digs his hands into the motors of the tractors and trucks on the farm. We speak with him at the farm office, just a few steps from the strawberry fields. On the wall there are posters of Emiliano Zapata and Mexican bullfighters, and a map of the state of Michoacán. The more we speak with Miguel, the more we hear his anti-union and clearly right-wing philosophy. "I am not a Democrat or a Republican," he tells us, since he is not yet a citizen (he's on the waiting list). "But if I could vote, I wouldn't be a Democrat." More than anything else, though, Miguel considers himself an "American." And, of course, he is: just a different kind of American than the kind we're used to encountering on the migrant trail. Miguel's is the classic "up from the bootstraps" story. He tells of the terrible conditions he encountered in the fields of Watsonville when he first arrived–the lack of bathrooms and drinking water, the white patrones (when he speaks derisively of white Americans, he calls them "yanquis") cracking the proverbial whip over the brown peons. But he looks upon today's migrants and shakes his head. "They need a change in mentality," he says. "I'm in this country, my kids were born here, I contribute to this community... these guys save their money to build homes back in Mexico. They should stop resisting feeling American." "American" for Miguel comes down to letting go of Mexico. Allowing new roots to sink into U.S. soil. English. Citizenship. Political participation. "To be an American is to be in this community and give to it. Go to city council meetings and get involved and not just play socccer." "We start living out of our memories," says Miguel. "The migrants go back home and tell spectacular stories... 'I made $120 in one day!'... and when we're here we don't want to be American, we say, 'la raza,' we say, 'Chicano.'" He pronounces the radical term with pronounced distaste. But there are times when Miguel does sound quite... well, Chicano–at least in the cultural sense. In between his anti-union diatribes ("The UFW paints us all like 'poor little peons'... they're just ouf for power for themselves."), he'll return to his own youth and his bitter memories of the "yanquis.'' "The boss was always white." He recalls that even in Mexico, the elites were white too. But, he says, "as anti-American a I am, I am now one of them." And yet... Miguel christened his first son with Mayan names: Quitze Balam, which from Indian tongue translates as "smiling tiger," meaning that his son's American friends will always refer to him in the ancestral language. What to make of Miguel Ramos? As adamant as he is about being "American," there is clearly a split in his soul. And now finds himself in the thick of union politics, on the side of the line usually populated by the very "yanquis" that he loathed–still loathes.

He does not admit it openly, perhaps he cannot admit it even to himself, but this must be a painful irony. He has staked out a very lonely territory: at odds with the prevailing politics of "his people," he is still obviously the odd man out among the growers of the Pájaro Valley, who are mostly white, whether or not he shares their politics. From the doorway of the office we can look out into the fields and see the workers bending over the long rows of mint-green leaves in the cold, gray, drizzly afternoon. Working with both hands, each worker rapidly snips a few berries from the plant with quick flips of the wrist, carefully stacks them into the cardboard bin, and then pushes the small iron cart another few feet down the row through the increasingly slimy earth. The workers are wrapped in garbage bags to keep from being soaked through to the skin. "Those are our disposable raincoats," Miguel says. Miguel

has somewhat of a patrician air about him, a kind of Old World, patronizing

benevolence cloaked in conservative American style. We cannot ascertain,

for this project, whether the UFW's allegations against Miguel are true.

What we do know is that although Miguel Ramos and Reyna Guzmán

are political opposites, their existential dilemma is essentially the

same. _________ Tomorrow is Joe's birthday, but I help him celebrate tonight. After days of diner food for me and health-store minmalism for Joe, I splurge and invite him to dinner on Pacific Avenue in Santa Cruz, the main drag of book stores, cafes and restaurants. (Earlier in the day, Miguel Ramos, apprised of the occasion, gave Joe a carton of strawberries, along with two Cuban cigars–authentic Cohibas). The transition from the fields into the time-warp of Santa Cruz is a jump-cut that leaves me edgy–half depressed, half raging. Sometimes I think that this is a result of doing everything I can to view the world from the migrant perspective. Other times I'm not so sure if it's the migrant POV that causes me to see the at middle-class whites sitting down to a fancy dinner which was picked, cleaned and cooked by brown servants; maybe it's just my own conflicted relationship between my "white" and "brown" selves.

On

Pacific, we run into a surreal crew of street characters that could

only appear in California. Skate rats–sans skateboards,

since there are strict ordinances against skating in downtown Santa

Cruz–crowd around us as Joe snaps street scenes. One kid, who has

the face of Jimi Hendrix tatooed on the inside of his forearm, starts

jamming on guitar for us. An aging, bulging hippy dressed in tie-die

garb prances past. Girls with pierced ears, noses, lips and navels.

It's Haight-Ashbury and Telegraph Avenue and Venice Beach, circa 1967,

all over again. _________ Joe and I have moved from the Barrios Unidos house over to the home of Reynaldo Barrioz, a Chicano cultural activist who lives in a charming two-bedroom home in Santa Cruz, just a block away from the boardwalk. He is part of a crew of Latino artists and intellectuals, including Manuel Rivas (lately of Barrios Unidos, but also a radio programmer and a fair player of Mexican folk music), Julie Reynolds (an honorary Mexicana after years of activism and editing El Andar, a local Latino publication that now has set its sights on going national), Jorge Chino, also of the original Andar crew, who just completed coursework at the Harvard Business School (in hopes of preparing the publication for the new world economy, no doubt), a young photog named Paul Meyers, who is making a name for himself with his gutsy style, hanging out in migrant bars locally and in the conflictive zones of Chiapas... In short, we are among the typical multi-ethnic California art crowd. We party at Reynaldo's house, where an African American dancer named Bhavananda, who is dating a Dutch photographer named Janjaap Dekker, salsa's up a storm with Julie, where Reynaldo rhapsodizes about a Japanese taiko-drum workshop he attended earlier in the day, where I move in and out of Spanish and English, where Joe suffers for his Leica, which slipped off his shoulder outside Reynaldo's house and hit the pavement lens-first, although he comes out of the funk later in the evening and gives a rousing inspirational sermon to young Paul, who's about to embark on a new tour of Mexico (travelling by train burro from Mexicali all the way to Chiapas). "Yo, duke," he says, in his inimitable Brooklyn-ese, "you need to improve on composition, you really need to work on that composition, but most of all, you need to have some self-confidence, eh? Get in there day in and day out and stick with it and believe in yourself, even when you get depressed, and you'll get depressed, no doubt about it, you'll have days when you won't even want to crawl out of the hotel and walk into people's houses and into people's lives and into people's shit.... but you'll do it.. and if you don't do it, I'll come down there and kick your ass until you do do it."

|

|||