|

| Case 8 / 17 |

|

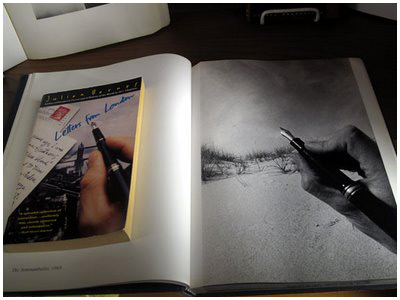

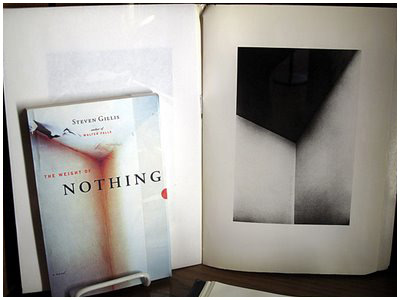

Display Case 8 (Gibson, Kertész)

By concentrating on the visual fragment and artfully intentional, edge-conscious composition, Ralph Gibson has, for more than thirty years, produced photographs which elicit in the viewer a sense of déja vu (the title of one of his early monographs); they seem at once fleeting and hyperreal, mysterious and mundane. While suggesting the presence of a narrative, they in fact reveal very little. Despite, or perhaps because of these qualities, Gibson's vision has become a much imitated stylistic trope on photographic book covers from the mid 1980s into the present.

|

|

|

The two covers here call to mind two images from his second, and perhaps most important, monograph, The Somnambulist.

Title: Letters from London

Author: Julian Barnes

Publisher: Vintage International 1995

Designer / Illustrator: Susan Mitchell (Art Direction)

Photomontage: Jenny Lynn.

|

Title: The Weight Of Nothing

Author: Steven Gillis

Publisher: Brook Street Press 2005

Designer / Illustrator: Not listed.

|

|

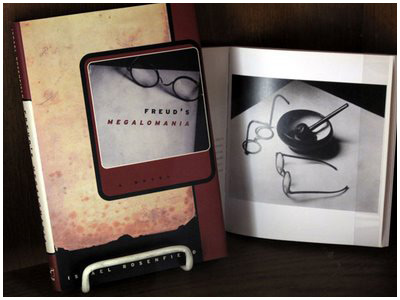

Title: Freud’s Megalomania

Author: Israel Rosenfield

Publisher: W.W. Norton & Company 2000

Designer / Illustrator: Debra Morton Hoyt

Photographer: Ed Marquand.

|

In 1926, André Kertész made a series of photographs in Piet Mondrian's Paris studio. Modernist in form, they also serve as symbolic portraits of this pioneer of abstraction. In particular, the image Mondrian's Glasses and Pipe isolates dark objects (Mondrian's pipe, a shallow bowl and two pairs of his signature round spectacles) against the white ground of what is most likely a tabletop (Mondrian's own work, of course, was much more compositionally rigorous than that of Kertész: He would never have allowed, for example, diagonal or round shapes to corrupt the theoretical purity of his compositions).

In Ed Marquand's cover image for Israel Rosenfeld's book, Freud's round eyeglasses and the white triangular background echo Kertész. There is no pipe in the picture, but Freud preferred cigars, and to include a cigar on the tabletop would be, well, too freudian. Instead, there is the title text, in correct perspective, which the glasses seem to be observing as if it were a patient on a couch.

It seems unlikely that Marquand would be completely unfamiliar with Kertész's Mondrian pictures, but let us assume for the sake of argument that he had never even heard of Kertész. How, then, do we parse Marquand's personal and intuitive sense of form, tone and balance from the Platonic forms; ie, the visual templates that float in the ether of our collective subconscious? In simpler terms, how do we explain the coincidence?

In large part, the question is rhetorical. To actually explain the coincidence, if there was a coincidence, might be interesting and possibly illuminating, but ultimately a footnote to the larger issue of how the past influences the present.

|

|

Write your comments:

|

|