|

"Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is . . . the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own. "

RICHARD AVEDON

|

|

| Back to Magazine |

Articles

|

|

Richard

Avedon's In the American West |

|

"Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is . . . the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own. " RICHARD AVEDON |

|

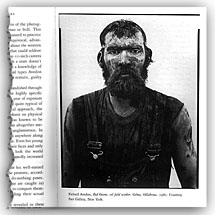

No one has smiled in an Avedon portrait for a long time. If there was pleasure in their lives it left them in the act of posing, or rather, confronting his lens. One sitter, de Kooning, told Harold Rosenberg that Avedon "snapped the picture. Then he asked 'Why don't you smile?' So I smiled but the picture was done already...." The photograph of de Kooning and the quote appeared in Avedon's Portraits (I976), an image-gallery of famous people in the arts and media. A disproportionate number of them look either snappish or torpid and tired . . . oh so tired . . . unto death. At the end of that book, in a suite of shots that record the progress of his father's cancer, the subject is described as literally wasting away. But this is a progressive account not so much of the flesh dying off, but more of his father's terrified knowledge of his decomposition - a conclusive rush of dismay that gives Portraits its unstated theme. Avedon's most recent portrait effort, In the American West, published by Abrams in I985, furthers that theme, once again by a characteristic emphasis at the end of the book. There, in studies of slaughtered sheep and steer, he insists upon such details as glazed and sightless eyes, blood-matted wool, and gore languidly dripping from snouts. As his father was the only unprominent person in the first campaign, so the animals are the only nonhuman subjects in the second. It's as if Avedon were each time underlining his philosophy by breaking his category. Adjoining the guignol presences of the animals are ghoulish images of miners and oil-field workers, as befouled by the earth as the animals by their spilled entrails. Avedon's portraiture of "ordinary" westerners is on the whole darker and more cutting than his earlier work. It's essential to the effect of the current subjects that they be presented as unaware of his designs on them. For Avedon's program is supraindividual. He wants to portray the whole American West as a blighted culture that spews out casualties by the bucket: misfits, drifters, degenerates, crackups, and prisoners-entrapped, either literally or by debasing work. Pawns in his indictment of their society, his subjects must have thought they were only standing very still for the camera. Even those few in polyester suits who appear to have gotten on more easily in life are visualized with Avedon's relentless frontality and are pinched in the confined zone of the mug shot. In photography, this is the adversarial framework par excellence. He could rely on knowledge of this genre to drive home the idea of a coercive approach (which he frankly admits), and of incriminated content. But why should he have imitated a lineup? And why, since this is his personal vision, should he refer to an institutional mode? The answer to these questions should probably be sought in the politics of Avedon's career, or rather, his career in the politics of culture. With him, style has always been understood as political expression, and the will to style but a reflection of the will to power. Translated into photographic terms, this becomes a matter of visually phrasing the relations between the subjects and the photographer. For example, either the sitter can be depicted as apparently possessing the means to act freely, or the photographer can be perceived as free in the exercise of control over others. In his fashion work for over thirtyfive years, Avedon configured the myth of the hyper-good life of the ultramonied in the bright expressions and the buoyant gestures of expensively outfitted women who flounce through a blank or glittering ambience where there is always enough room for them to open their wings, even in close quarters. No one had more success in vectoring the physical ease with which splurge maneuvers. No one could fake a more lacquered spontaneity. Unquestionably Avedon called the shots in the studio, but his was the kind of work in which mastery nevertheless had to disguise itself, hold itself in check. Though they were literally his creatures behind the scenes and in the throes of picture production, the fashion models were imaged to have a magnetic, even commanding effect. The conceit of the genre asserts that subjects are constant narcissists and photographers are professional adorers. Fabricated through the collective resources of a large and nervous industry, the final spectacle, a self-centered object of regard, was something that existed only to lift up and draw in the gaze of the viewer. The high-fashion photograph mimics a situation in which the viewer is supposed to be captivated by styles of material display. Of course its commercial message was thoroughly bonded to the psychic lure and social symbolism of the picture. All those with craft input into the fashion image were contributing to a mercantile semblance of a court art in a democratic society. In the late forties and early fifties, there developed an American market for an idiom of literal swank and sniffishness. Avedon led the way in adapting this largely continental mode more appropriately to our manners. He made his figures approachable, innocently overjoyed by their advantages, as if they were no more than perpetual young winners in life's lottery. It was Avedon, too, who set the pace for contemporary narrative scenarios of fashion display. Into the sixties he managed to waft via the faces of his mannequins the sense that their good fortune had hit very recently - say the second before he opened the shutter. When unisex became chic, and fetishism permissible, he filtered some of their nuances into his design. He could also suggest that the glamour of his models drew the attention of sports and news photographers, whose styles he sometimes laminated onto his own. (This was a snap for someone who grew up on Steichen and Munkacsi, and knew about Weegee.) Insights into the crossover of genres and the convergence of modern media gave Avedon's work its extra combustive push. He got fame as someone who projected accents of notoriety and even scandal within a decorous field. By not going too far in exceeding known limits, he attained the highest rank at Vogue. In American popular culture, this was where Avedon mattered, and mattered a lot. But it was not enough. In fact, Avedon's increasingly parodistic magazine work often left -or maybe fed- an impression that its author was living beneath his creative means. In the more permanent form of his books, of which there have been five so far, he has visualized another career that would rise above fashion. Here Avedon demonstrates a link between what he hopes is social insight and artistic depth, choosing as a vehicle the straight portrait. Supremacy as a fashion photographer did not grant him status in his enterprise -quite the contrary- but it did provide him access to notable sitters. Their presence before his camera confirmed the mutual attraction of the well-connected. Unlike the mannequins, most of the sitters had certified personalities, and this perked up Avedon's interpretations with extra dividends of meaning. The early portraits worked like visual equivalents of topics in the "People are talking about . . ." section in Vogue; they fluttered with cultural timeliness. When he showed Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller lovingly together, it was as if each of them took manna from the other in a fusion of popular and highbrow icons. The first book, Observations (I959) with gossipy comment by Truman Capote, spritzes its subjects with an almost manic expressiveness. They are engaged at full throttle with their characteristic work, so that the contralto Marian Anderson, for instance, has a most acrobatic mouth. These pictures were engendered well within the fashion mold (publicity section), but they led gradually to a break into a new, anxious politics of the image. Avedon's second book, Nothing Personal (I964), tries to evoke something of its historical moment, although it would seem hard to suggest the duress of the sixties through portraits alone, even when arranged in narrative sections. It opens with foldout tableaux of wedding groups, in which a number of ordinary people rehearse their festiveness, as if they were models. There after, we get sitters known for ideological heaviness, positive or negative depending on the readership: the Louisianian politician Leander Perez, George Lincoln Rockwell, Julian Bond, and so on. They scowl, salute, or look clean-cut; that is, they are made to impersonate their media image with breathtaking simplicity and effrontery. One symbol is assigned per person, and one thought is applied per image. Almost at the end, Avedon treats us to a group of harrowing, grainy action closeups of inmates in madhouses, and he concludes the book with happy beach scenes.

|

|

|

|||

|

|

page 1 |

|

|