|

|

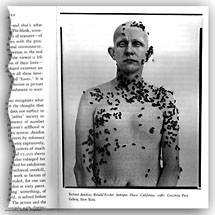

But the question remains: what is convincingly revealed in these images? I, for one, am persuaded of the grumpiness of most of the sitters at the moment they were photographed. One sees this expression often in photographic culture, when people aren't getting help from the stranger behind the camera, and don't know why he should be trusted. It's a kind of squint, and it hardens them. In a book containing I06 pictures of westerners, this arid psychological atmosphere prevails so completely that it rules out the freshness of any open, one-to-one human contact. The subjects are individuated according to their varied circumstances and histories, but not by their moods. Whatever public foreknowledge might have made it difficult for Avedon to obtain his results in his own social circles during the first half of our decade, they could be brought off more easily among any group unaware of his national reputation, such as these somewhat defensive but unsuspecting westerners. Their need to plead their case went deeply, he says, but "the control is with me." If his insistence upon this control is necessary to legitimate himself as a realist artist, no matter at whose expense, he nevertheless fails to accomplish realist art. Again, his sophistication about photographic pictures prepares him to encompass and accept this judgment. As he introduces the western gallery, Avedon writes, "The moment {a} fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth." How remarkable that his critics have not thought to quote him a little further on in this statement, where the deep, internal conflict of Avedon's portraiture asserts itself. On one hand, he arranges it so that the sitter can hardly shift weight or move at all, supposedly because the camera's focus won't allow it. The hapless subject has to learn to accept Avedon's uncompromising discipline (as if the lens and the photographer were the same). On the other hand, "I can heighten through instruction what he does naturally, how he is." In the end, "these strategies . . . attempt to achieve an illusion: that everything . . . in the photograph simply happened, that the person . . . was never told to stand there, and . . . was not even in the presence of a photographer." One either remains speechless upon reading this total denial of his working program in the American West, or one sees that it applies covertly to fashion photography. Such stridently mixed signals and elemental confusion about self-process have something to say to us about the derisive qualities of the work itself. I think not only of the fact that voyeurism is the chic metaphor in fashion (none of the models are supposed to be aware of the photographer), but also that fashion has always been an imagery of material display -and that's what Avedon's western portraiture consciously amounts to. The blank, seamless background thrusts the figures forward as islands of textures of flesh, certainly, but also of cloth. Nothing competes with the presentation of their poor threads, nothing of the personal environment, nothing that might situate, inform, and support a person in the real world, or even in a photograph. At the same time, the viewer is left in no doubt about the miserableness and tawdriness of their lives- for their dispiriting jobs or various forms of unemployed existence are duly noted. An ugly comparison is invited between all these havenots and Avedon's previous and much better defended "haves." It is one thing to portray high-status and resourceful celebrities as picture fodder: it is quite another to mete out the same punishment to waitresses, ex-prizefighters, and day laborers. Where is the moral intelligence in this work that recognizes what it means to come down heavy on the weak? Even the thought that such hard luck cases might arouse class prejudice does not surface in the book's text. All that would be required for "polite" society to imagine these subjects as felons would be the presence of number plates within the frames. In the mug shot, the sitter's selfhood is replaced by an incriminating identity in a bureaucratic system. Avedon has gained a cheap, enduring dominion over his sitters by reference to this mode, but executes his pictorial versions of it very expensively, and therefore, innovatively. He not only used a view camera of much greater optical potency than needed and exposed around I7,000 sheets of film in "pursuit of 752 individual subjects";(1) he also enlarged his photographs to over life-size and had them metal-backed for exhibition in art galleries and museums. The disproportion, technical overkill, and sheer obsessional freakishness of this campaign work as factors of stylistic insistence. And without question, he succeeded, for one can definitely recognize any of these pictures as an Avedon at sixty paces. For fashion photographers, the problem of "saying" something, of having any conceptual obligation to picture a world, is solved before any film is exposed; they know who the client is. The action and the enjoyment of fashion photography is bound up entirely with distinctions of craft, flair, and setting - the equivalents in their commercial context of imaginative vision in an artistic one. For all their harshness, Avedon's portraits belong to the commercial order of seeing, not the artistic. Just the same, the western album is his most arresting book. I am thoroughly downcast by his terrible perspective on the West (in a background text Laura Wilson, his assistant, more or less implies Avedon's special receptivity to damaged subjects), but that is his right. Obviously, whole spheres of western culture - the sun-belt retirement communities, the new wealth grown up through oil and computer development, the suburban middle class -are ignored in Avedon's gallery. He is definitely obsessed by a myth based on geographical desolation, rather than engagement with any real society. Just the same, those who complain about his unfair visual sampling are quite off the mark; let them tell us what sampling is fair. But if I ask what is the principle of this sampling - for example, personal animus, political critique of western culture and conditions, or humanist compassion for social casualties - I don't get any legible reading at all, and suspect that there isn't one. It's not that the subjects don't incite judgment or sympathy - they do that automatically because they're human and we're human. Rather, Avedon counts on their shock value, on this level, to get us absorbed by the way they look. It's certainly true that the picture of the blond boy exhibiting the snake with the guts hanging down is a sensational image. Likewise, the hairless man literally coveted with bees. And who can forget the Hispanic factory worker with the crisp dollars cascading down her blouse, or the unemployed blackjack dealer, with a face made of dried leather and bristle, whose sport jacket is a tantrum of chevrons? Nothing seems to come out right in these faces, and so many others, that have a breathtaking oddness. They make terrific pictures. In I960, Avedon did a real mug shot of the Kansas murderer Dick Hickock, protagonist of Capote's In Cold Blood. He printed it next to a larger one of Hickock's father (taken the same day), in the Portraits book. Here is some evidence of an avid look at the genetics of American faces for whatever might be reckoned as pathological in them. In the current gallery, that pathology seems to have come home to roost, at such close graphic quarters that it's a relief to know that these are only pictures, and the subjects won't bite. Pictures may be only their mute selves, but for Avedon they are everything, a totality. The photographer thinks that you ultimately get to know people in pictures, as if there is some arcane, yet clinching knowledge to be gleaned from the image. Strangely enough, it had been the inadvertent resemblance of his earlier western portraits to nineteenth-century ones that led the Amon Carter Museum of Fort Worth to commission Avedon to do this series. If any such work is recalled to me, it would be medical photography of the last century. Doctors had sick people photographed to exhibit the awesome hand of nature upon them. Later, the subject might be lesions. Avedon photographs whole people in the "lesion" spirit. In the New York Times of December 2I, 1985, he asked, "Do photographic portraits have different responsibilities to the sitter than portraits in paint or prose, and if they seem to, is this a fact or misunderstanding about the nature of photography?" Well, if he had to ask, the question certainly indicates his misunderstanding of the medium. But more than that, the question symptomizes a failure of decency that no amount of vivid portrayal will ever redeem, because the portrayal and the failure are bound together in the malignant life of the photograph, each a reflection of the other. |