Mark

Haworth-Booth, curator of photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum

in London, guides us with patience and great care through the intricacies

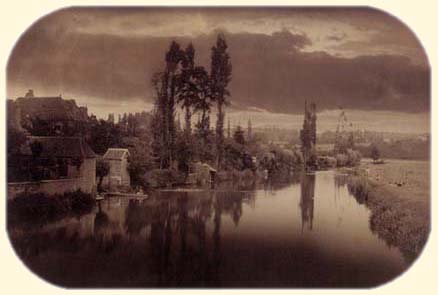

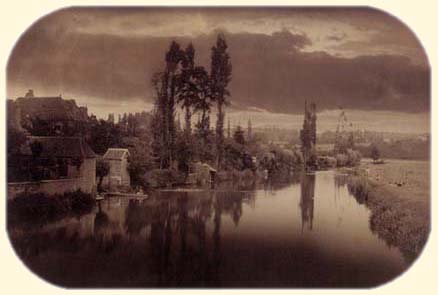

of what Camille Silvy had accomplished in his 1858 image named "River

Scene, France" by creating an image composite from various negatives.

In his revealing study, Haworth-Booth narrates how Silvy's

"River Scene, France" may appear to have been taken with a

wide-angle lens, and goes on telling us "but this effect

results in part from the optical effect of the oval format.

A rectangular mask placed over the photograph establishes a

quite different general impression. The clouds, as they do

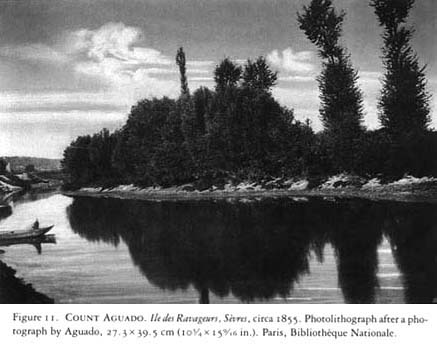

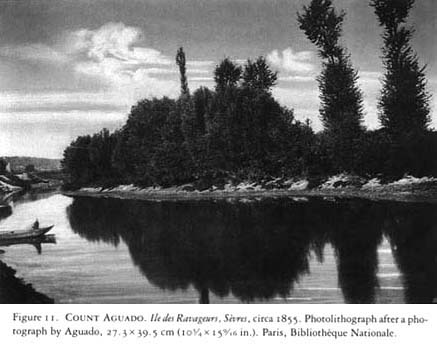

in the photolithographic version of Aguado's 'Ile des

Ravageurs', greatly accentuate the perspectival depth". The

difference clouds make to a landscape was well described by

a contemporary critic: "A sky should convey the effect of

space, not surface, the eye should gaze into, not upon it,

and instead of coming forward and throwing back every other

object it should retire and bring the landscape into

prominence. Landscapes without skies, with only a uniform

white tone above the ground, were found wanting by critics.

They lacked atmosphere. But the blue sensitive negatives of

the time made landscapes with skies an almost impossible

challenge."

Silvy apparently solved the problem by photographing a

landscape and the sky separately, on separate negatives,

and probably on different occasions and in different

places. He joined landscape and sky at the printing stage.

This process had already been publicized widely by

Hippolyte Bayard in 1852. This method became a widely

accepted practice at the time.

With great foresight, Mark Haworth-Booth consulted in 1982

with Ansel Adams, as to his interpretation of "River Scene,

France" and these were the words in the letter of response:

" You will note that there is a dark value in the trees

above the bottom cloud line. This indicates that the

masking was not done adequate in this area ( it is not

apparent in the trees to the right)". He also detected "something 'phoney' about the light-edged clouds along the

horizon; they look to me as they were retouched in." Adams

also thought that "the little shed on the left looks dodged

or 'bleached'". He pointed out that "there is no reflection

of the clouds, the water foreground has been burned-in and

the roof of the little shed is in the area of the main

burn-in, and consequently darker than expected.... The

right hand side of the picture is in a different light from

the left hand side. There is a definite 'dodging' area

above the roofs on the far left." Adams concluded, we are

told by Haworth-Booth : "It is pretty good optically. The

'old boys' did some remarkable 'cut and paste' jobs; I am

surprised that the green foliage comes through so

well....Apparently it was quiet water and very little wind

( if any)".

After reading these remarks I recently asked Sarah Adams,

if she thought that her grandfather would have taken to

digital photography, to which she responded:

"Yes, we believe Ansel would have been immersed in digital technology.

Several possible reasons:

a. More environmentally sound

b. Archivability / restoration of older negs

c. Greater access to color realm

d. The newness of new tools; recently learned that at the 1915 Pan-American

exposition in SF at the age of 13 he taught himself quickly the art

of typing and taught others at a booth!!?!:)

e. Access to photographic manipulating tools: dodging and burning, etc."

I was intrigued by her response, in particular to the last

sentence, where she refers to the tools of manipulation,

with the dodging and burning, leaving, as I see it, the

most important opportunities of digital transformations in

the realm of the etceteras. In an oblique manner however,

she does acknowledge all that can be accomplished with such

tools, as she leaves the door open with that very useful

expression that fits so well when we need to be imprecise,

etcetera.

I don't say this in a critical manner, because there is no

room for that; my observations relate to the anecdotal

value of how someone chooses to describe what promises to

be the biggest transformation of photography since it was

first discovered. She is certainly in plenty of good

company when it comes to describing the tools that promise

to unlock the future of photography as etceteras.

|