| We have all heard these arguments before, and what they all have in common as I see it is style over substance. To begin with, the idea that it's the pictures that should be trusted in order to defend a profession is not understanding the nature of photography in the first place. Why should anyone trust a picture, just because it's a photograph, that is shear nonsense. I don't see journalists all heated up because we disbelieve what people write about. I think on the contrary, they deal with the credibility issue by doing something that I have yet to see happen in the photojournalistic community, and that is, to actually confirm from a second source the information that is delivered. Actually the reverse happens, the image is used as a way of confirming texts, when in reality the picture can be as we now know, just as questionable a source as the text is. How much more sense would it make if that irate technology

coordinator from the Muskegon Chronicle would say "from

now on, what we are going to do, given that we are now more

conscious that any image can be altered, is to guarantee

our readers, that the content of the image satisfies the

same demands placed on our writing. The image is not to be

given credibility just because it's a picture. The

responsibility for guaranteeing the integrity of the

information is with the publication, not with the medium.

All pictures, such as with text, are confirmed from several

different sources when in doubt; otherwise it's the

photographer's responsibility to deliver an image with

integrity towards the events, which in turn will be

constantly monitored. We understand that integrity is not a

matter of how the picture was made, but what it's supposed

to communicate. Just as we don't oversee if the writers do

so by hand or type on a computer, our photographers are

free to use any tool they want. The veracity of an image is

not dependent on how it was produced, anymore than a text

is credible because no corrections were done to it. And by

the way, we shall also guarantee that the captions to a

picture will always be as accurate as any of the other

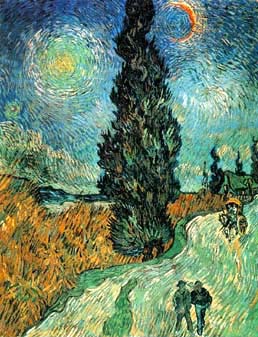

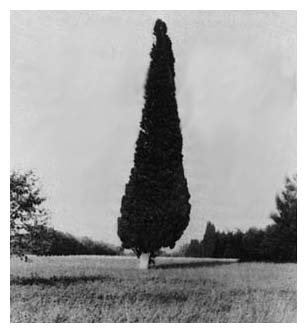

parts of our paper." It was the painting of a Cypress tree on the road to Auvers (which is reproduced here for you, courtesy of me being able to search and find it on the Internet, need I say more?). The writer tells us that a short time later he was in the south of France at Arles, the old Roman town ( and may I also add, now also a center for photography) where Van Gogh made many of his landscapes, when one morning he had a sudden desire to see the real Cypress trees that had inspired the painter. His inquiry led him first to the local librarian and then to the curator of ancient monuments, before he found himself at four o'clock in afternoon facing a "van Gogh" cypress. Here is the photograph that he took that day.

He tells us that the tree appeared massive, tremendously solid and substantial, at which point he realized how two-dimensionally flimsy and fragile the painting was. He thought how strange it was that thousands of people should wait in line to regard a flimsy image when they could come down to Arles and see the solid, real thing. But then a question arose: "Which is more real, the tree in the field or the image of the tree as interpreted by the painter?" For there were no people in line to see the tree in the field". He goes on "I have to admit that the tree in the stubbled wheat field was a disappointment. It had none of the fiery growth or dynamic color displayed in van Gohg's painting. Despite it's concrete monumentality it was just a tree, whereas the painting was the tree plus something else. It is obviously the 'something else' that draws the crowds, and that is the magnetic attraction of art". The Mexican poet Veronica Volkow wrote, "With the digital revolution, the photograph breaks its loyalty with what is real, that unique marriage between the arts, only to fall into the infinite temptations of the imagination. It is now more the sister of fantasy and dreams than of presence."

I believe photography has taken on a new lease on life, finding itself at new crossroads where the documentary image as well as the artistic expression will evolve on to new levels of magnetic attraction, where the image will be distributed in ways never seen or heard of before, telling the same old stories of mankind if you will, but in so many new ways that we shall find renewed inspirations. That is why for me this is the Renaissance of Photography. Los

Angeles, California |